So far we've taken a close look at the Cold War occupation of Berlin, as well as the most hated symbol of the Cold War, the Berlin Wall. Now what was life like outside that Wall, in Communist East Germany? We all know that people in the East were worse off than those in the West and had to live with heavy restrictions on their personal freedoms. Here we're going to see how ordinary East Germans lived their daily lives, thanks to Berlin's DDR Museum.

The DDR Museum, which I visited on September 7, 2020, has to be my favorite of all the museums I went through that weekend I spent in the city. While so many such museums are mostly artifacts behind glass and literal walls of text, this one really went above and beyond that, with plenty of hands-on interactive exhibits, presumably disinfected regularly.

This is one of East Germany's most (in)famous exports, a Trabant! Meant as the East's answer to the West's VW Beetle, this little box was a really awful car, considered "cardboard on wheels" by many. People often had to wait years to get one after ordering it. Despite all this, people got really attached to their Trabis and took great care of them, because for most of them, it was the only car they would ever get.

Want to know what it's like to drive a Trabi? The inside of the car is a driving simulator! You can only do this for about five minutes before it tells you that your tank is empty and it's time to let someone else drive it.

The first time I ever visited Europe was in 1997 when I spent a week visiting relatives in Hungary. Since that country, at that time, was less than a decade removed from Communism, there were Trabants everywhere all over the roads there. Their engines sounded like those of weed-whackers. Thankfully post-Communist countries have since moved on and those cars are pretty rare today.

So your long-awaited Trabi finally got delivered and you can finally take a trip somewhere in your own car. Vacations were prohibitively expensive out-of-pocket, so it was pretty common to get a government-subsidized trip to an approved destination. Of course such destinations were in Communist countries, hence the road atlas covering East Germany, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Romania, the Soviet Union, and Hungary.

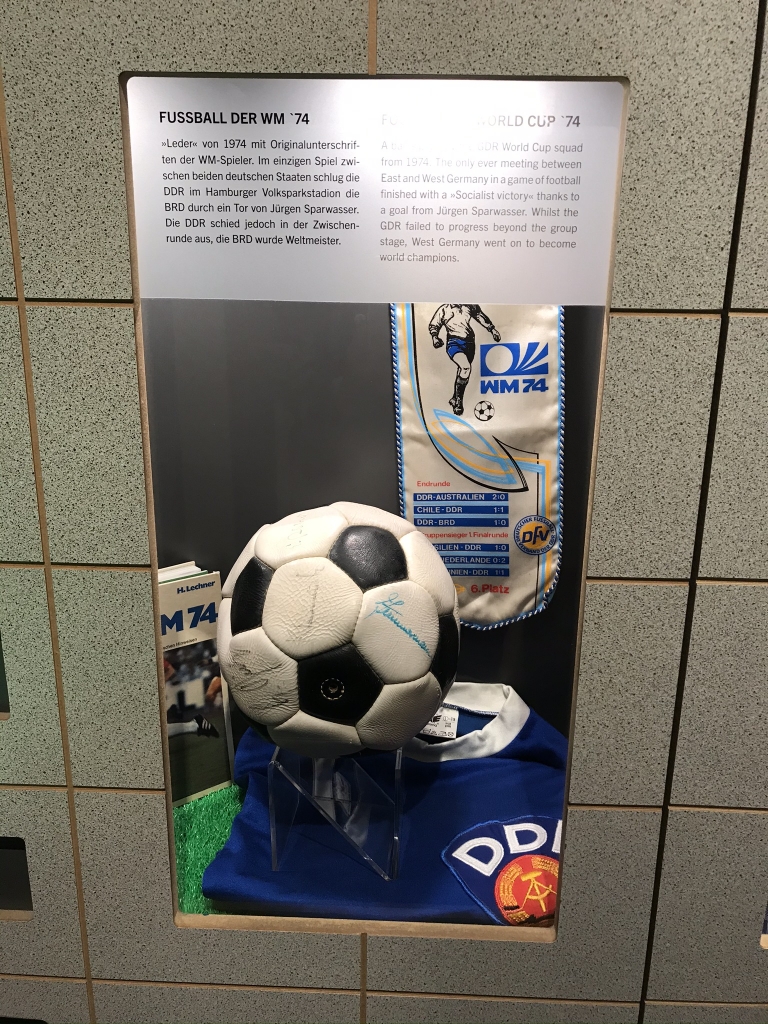

Part of an exhibit about East German sports, in which we see artifacts from East Germany's sole World Cup appearance in 1974. As I would later learn at the Fussballmuseum in Dortmund, East Germany actually beat the West in their only match thanks to Jürgen Sparwasser's famous goal. Despite this against-the-odds victory, the East never made it out of the group stage while the West, having the better team, went on to win the whole tournament.

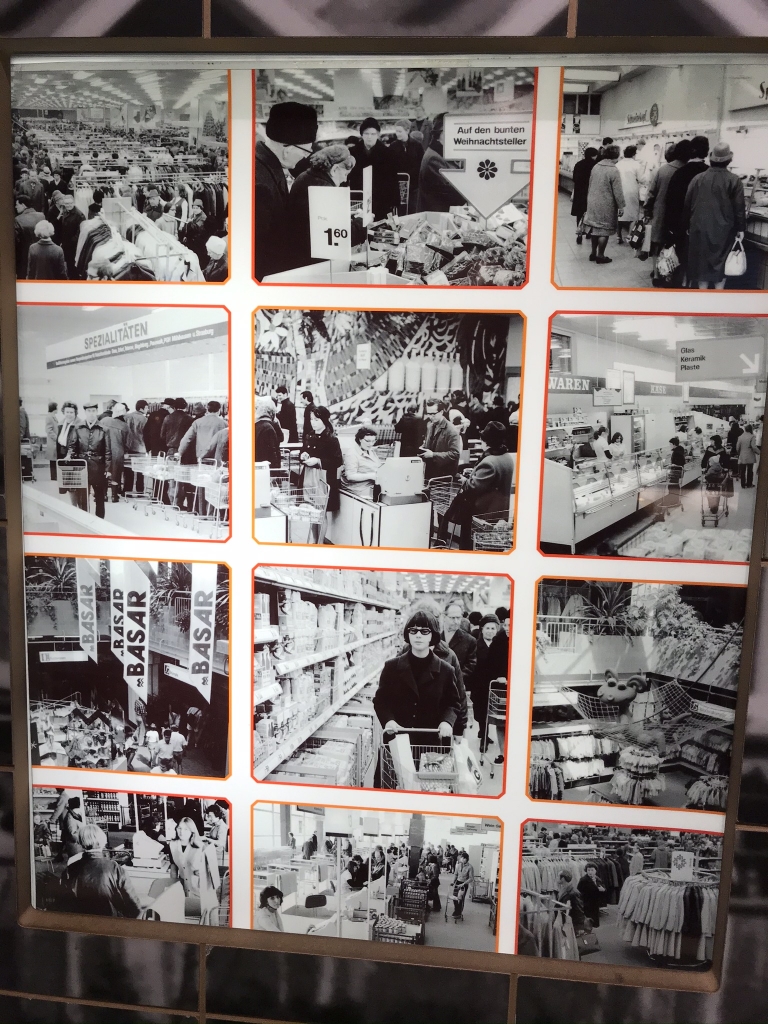

Inside various East German stores.

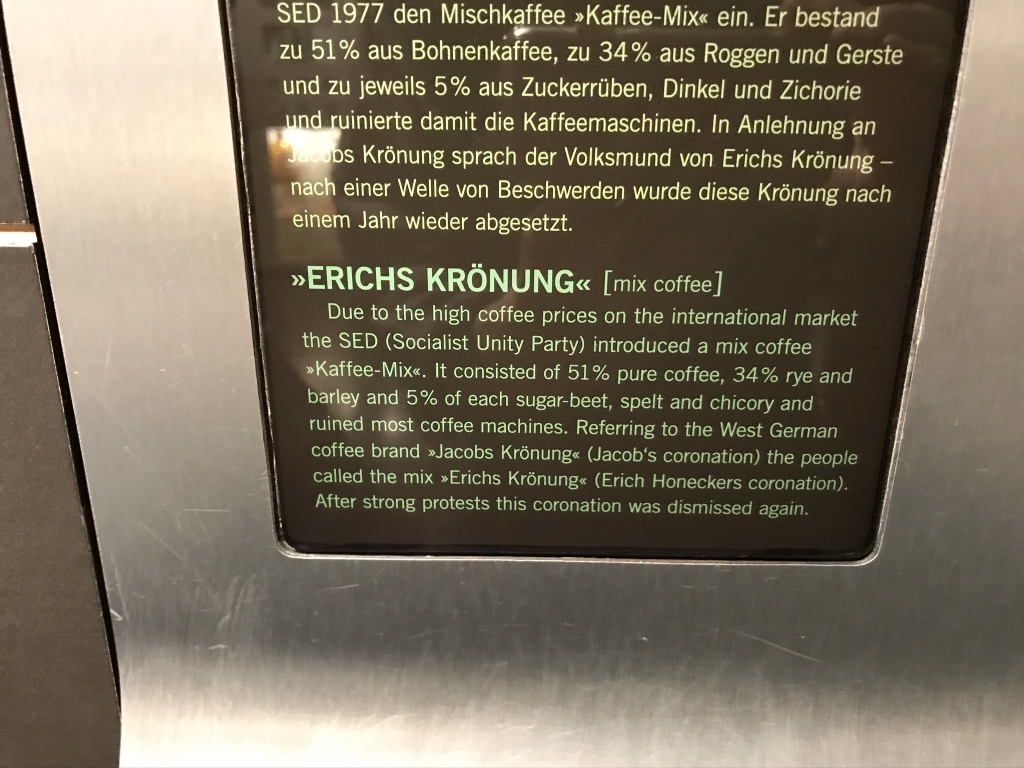

Even though this probably tastes horrible, I kind of want to try this.

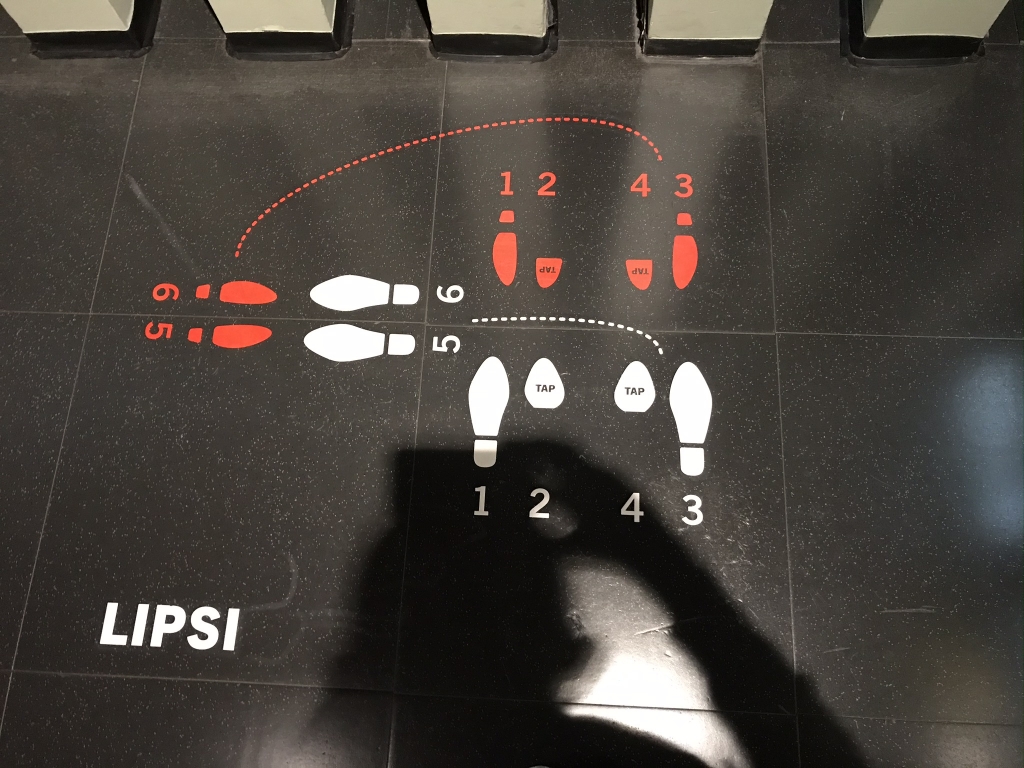

Since East German youth of the '50s could easily pick up American rock 'n roll music from West German radio stations, including those AFN stations operated by US troops, the Eastern authorities tried to push back against this. The Lipsi was a classic set of partnered dance steps the ruling Socialist Unity Party commissioned for that purpose, along with music it was meant to be danced to. The nation's youth had no interest in it, saying "Wir brauchen keinen Lipsi und keinen Ado Koll - wir brauchen Elvis mit seinem Rock 'n Roll!" (We don't want the Lipsi or Ado Koll, we want Elvis and his Rock 'n Roll!)

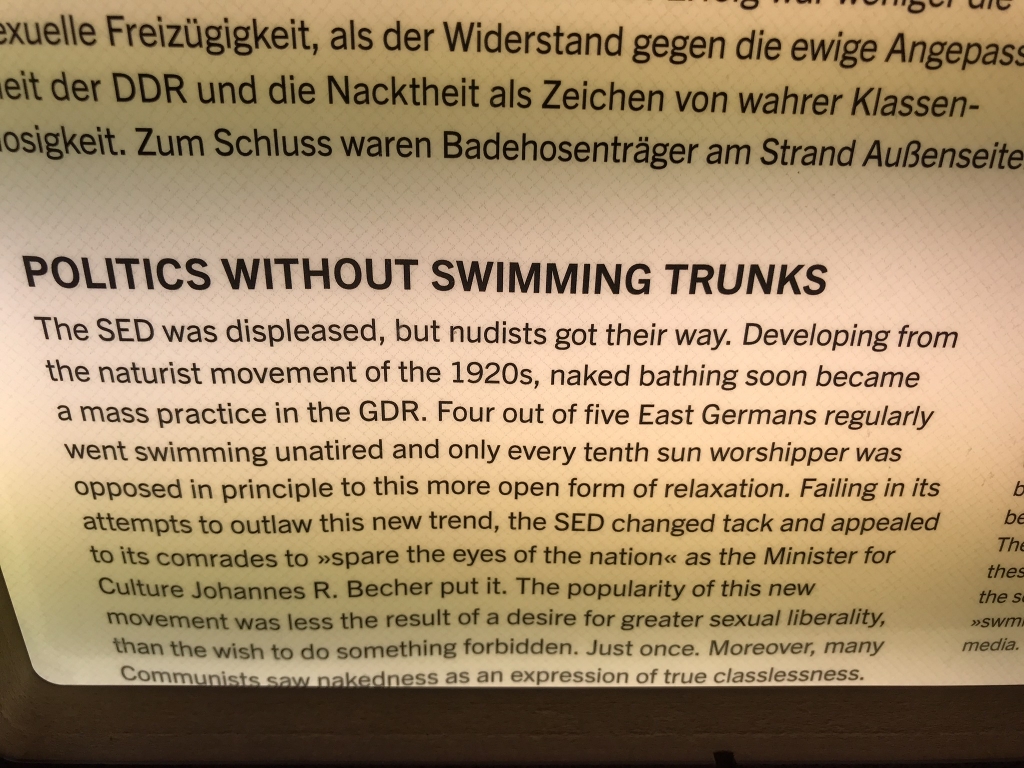

Here's something else about East German culture I didn't know about.

Now we move on to another large hall dedicated to East Germany's politics. Communist countries have legislatures which act as "rubber stamps"; that is, since there's only one relevant political party, all the real lawmaking is done behind closed doors by the Politburo--a council consisting of the top dogs in the country's Communist Party--and the legislature just approves, usually unanimously and without debate, whatever the Politburo submits to it. I use the present tense here because this is how the Chinese and North Korean governments still operate today.

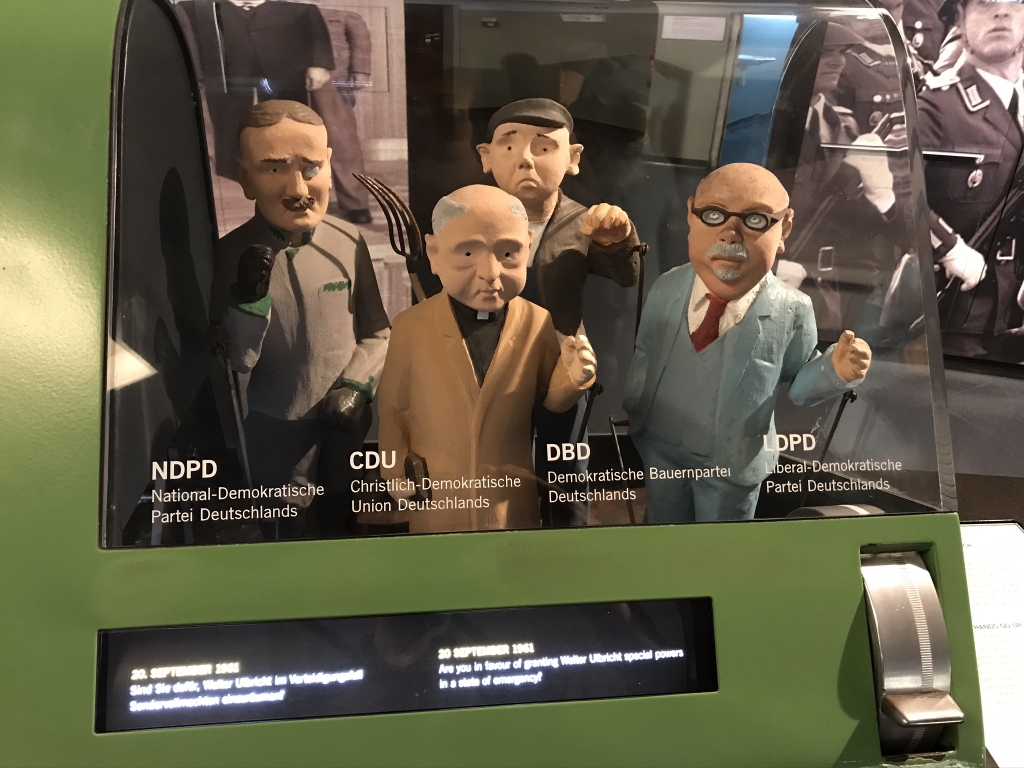

In East Germany, the rubber stamp legislature was called the Volkskammer (People's Chamber). It was unicameral--i.e. only had one house--and was dominated by the SED (Sozialiste Einheitspartei Deutschlands, meaning Socialist Unity Party of Germany), which was East Germany's version of the Communist Party. There were other parties, known as "bloc parties," which were meant to give the illusion of choice as each one appealed to a different segment of society. This was all a sham, of course, since the bloc parties were all in a coalition, the National Front, with the SED and just voted "yes" on everything along with them.

This box here illustrates what I just wrote up there. Each of these figures represents a bloc party: the National Democratic Party, the Christian Democratic Union, the Democratic Farmers' Party, and the Liberal Democratic Party. You turn that dial in the bottom right and see one resolution or law or another appear in the display across the bottom. Then you pull a lever on the left (not in the photo) and watch everyone's hands go up, because Volkskammer members voted "yes" on everything. One of the signs near here said that before the Volkskammer's only free election, the only time anyone ever voted "no" was in 1972 on a law legalizing abortion. There were not enough such votes to kill the bill.

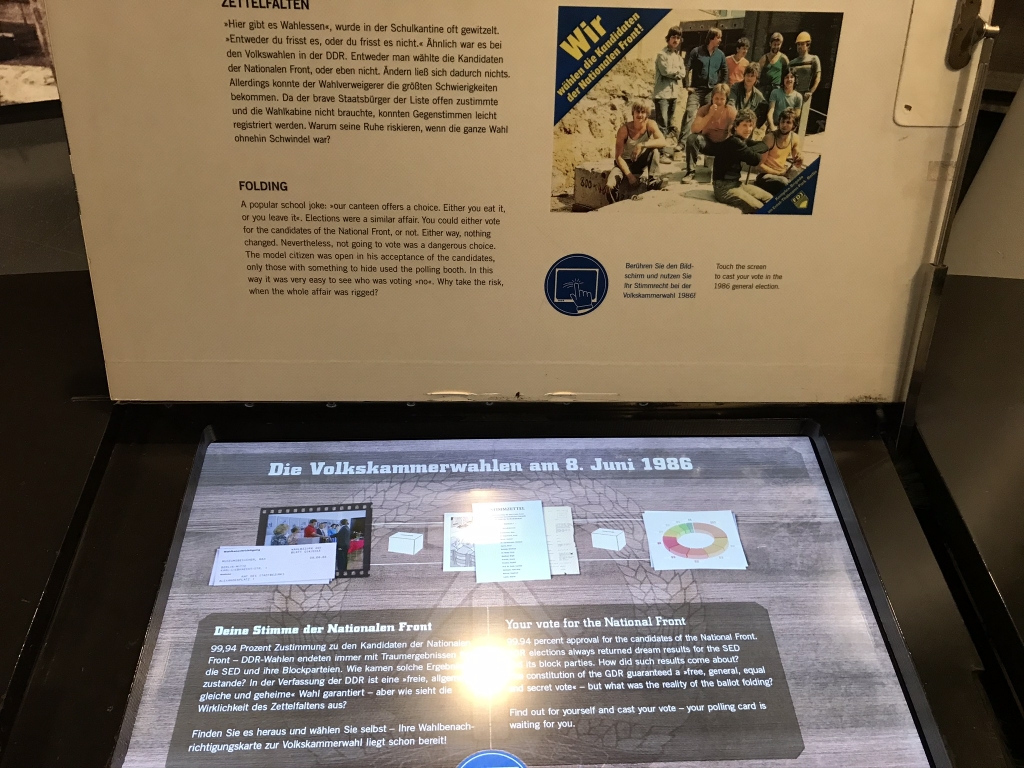

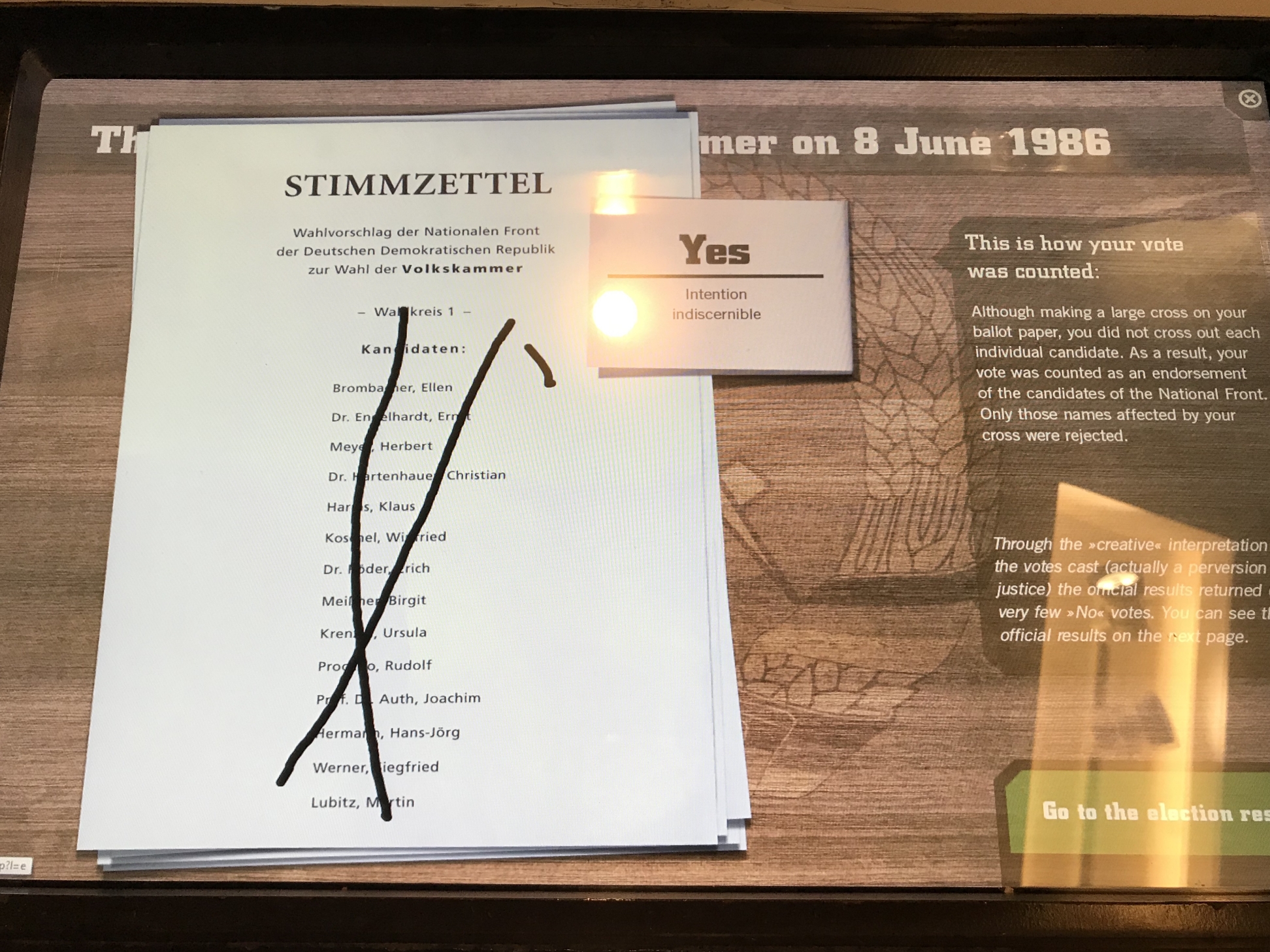

Elections for members of the Volkskammer were what we call show elections. The way they were described sounds quite similar to the way North Korean elections are still done today. Almost every eligible voter, except for those who wanted to make a dangerous statement by not voting, showed up at the polling place where they were handed a ballot, a piece of paper containing a list of candidates. There was only one candidate running for each office, you weren't actually choosing one candidate over another, just saying "yes" or "no" to each one...and it was really in your best interest to say yes to all of them. Since everyone technically had the right to cast a secret ballot, there was a single "secret voting booth" in every polling place, but really you were expected to simply fold the paper and hand it to one of the election officials, implicitly voting for all of them. For this reason, East Germans often referred to voting as "going folding." Or, you could walk over across the room to the secret voting booth and cross out the names on it, but this was about as dangerous as not voting.

This was part of an amusing game where you can participate in the election of 1986. First, I did this the "right" way, showing up at the polling place and folding the paper...

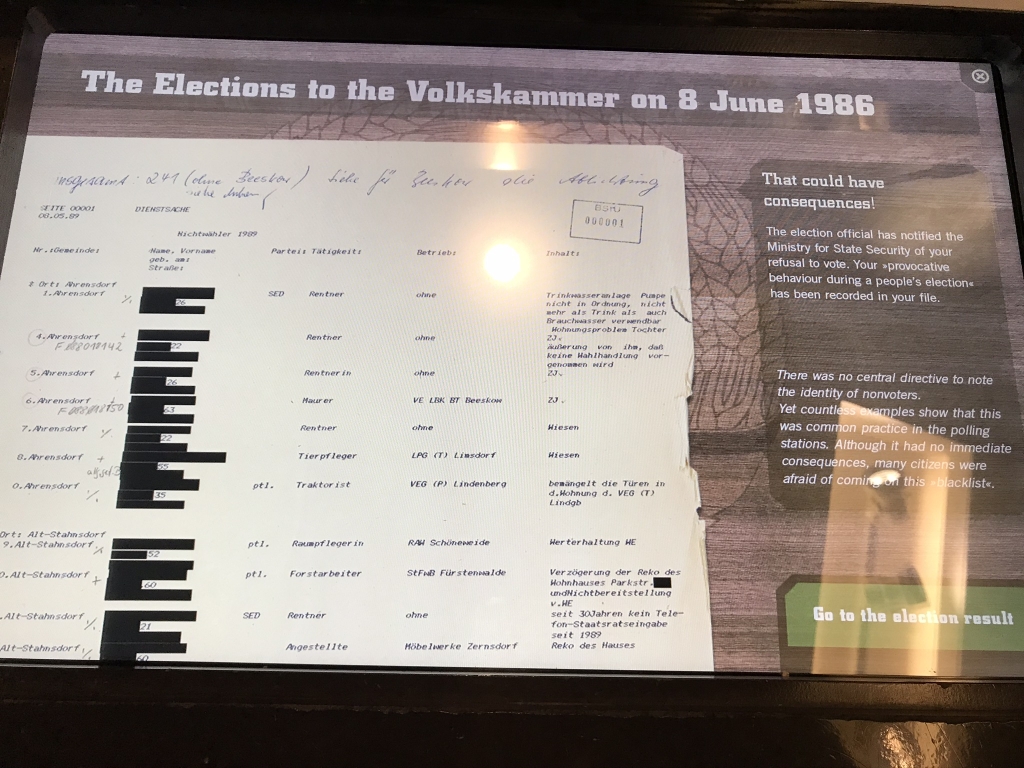

Then I did it a couple more times in "wrong" ways. Here, I refused to go to the polling place. Then someone showed up at my apartment with a mobile ballot box, and I refused to participate. They persuaded me to vote, and I refused to be persuaded. This screen came up next.

I did the game a third time, this time showing up at the polling place but using the secret voting booth. Here I got a screen saying "if you're using the secret booth, that means you have something to hide!" And apparently I couldn't hold my phone straight when taking a picture.

Then this screen came up to show that my actions didn't really affect the election anyway.

Egon Krenz--an election official who three years later briefly became East Germany's last Communist head of government--reading the results of the election, in which the National Front unsurprisingly won in a landslide.

The Volkskammer only had one free and fair election, which was in 1990. The resulting multiparty legislature served for only seven months before reunification, but for that brief time it actually performed the functions of a democratic legislature and was not the rubber stamp it used to be. For those seven months it could be said that the German Democratic Republic actually lived up to its name, or at least tried to. The last thing it voted on was to disband and join the Federal Republic of Germany (i.e. West Germany), which took effect on October 3, 1990, what is now called German Reunification Day.

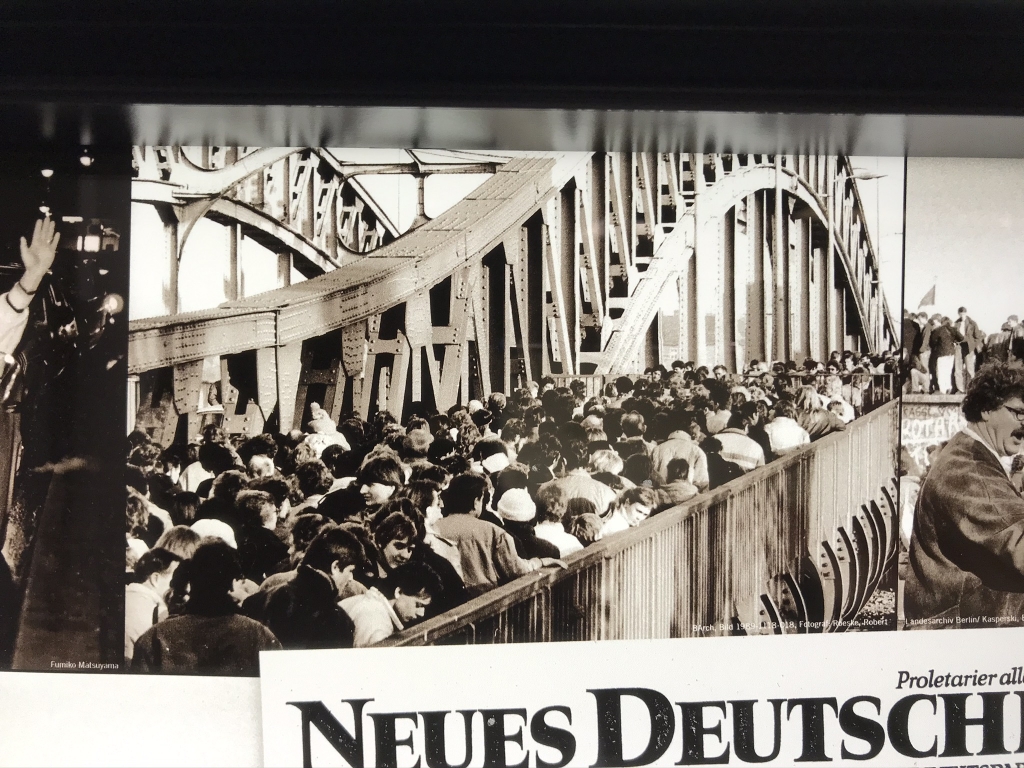

Hey, that looks familiar, like I was just there last night! It's Bösebrücke, the first hole in the Wall, where East Berliners could freely cross over to the West in 1989.

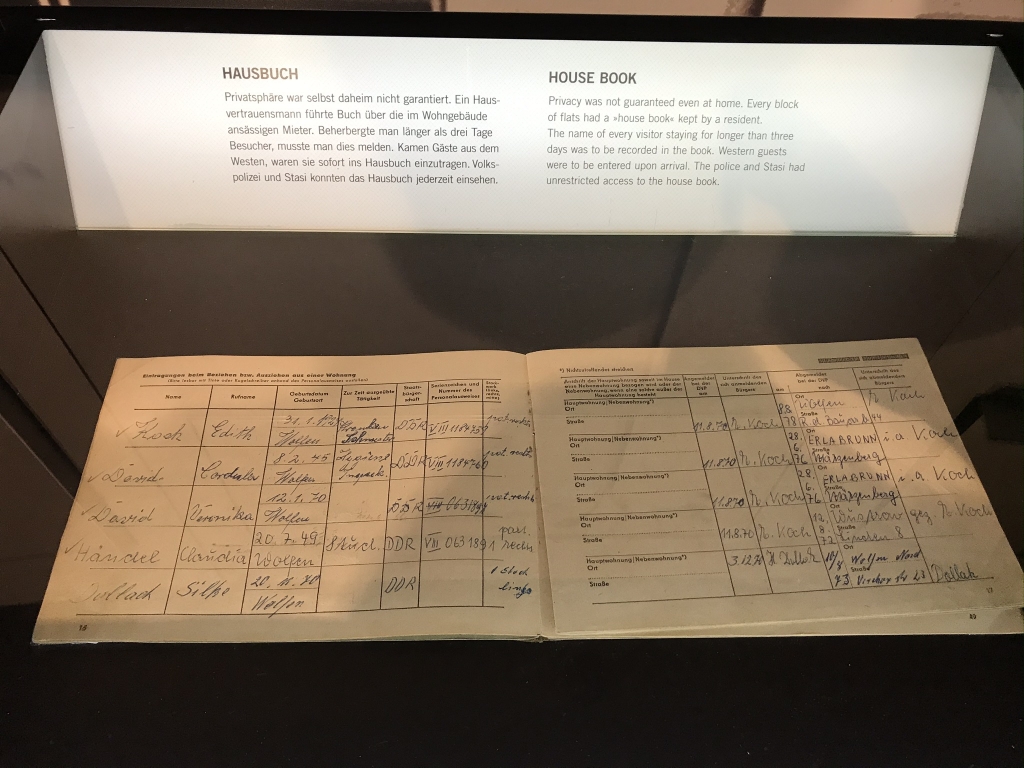

Privacy? What's that? If you visited anyone for more than three days you had to put your contact information in the "house book" which the authorities regularly went through.

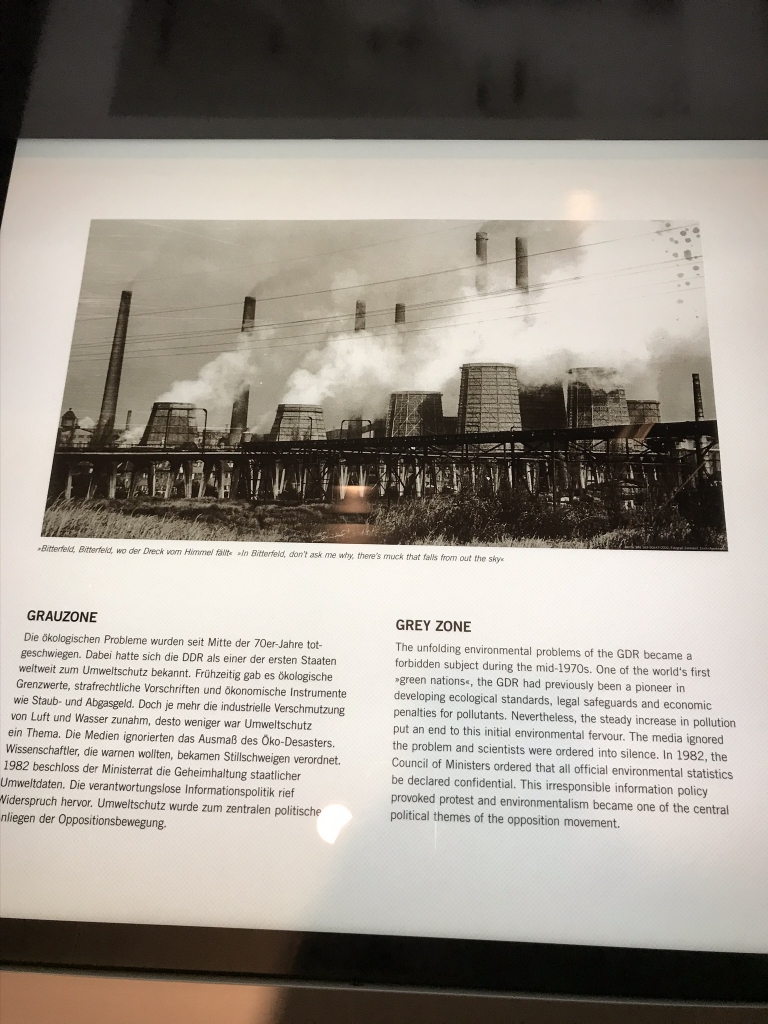

East Germany produced some serious air pollution, something their government knew was bad and didn't want anyone talking about.

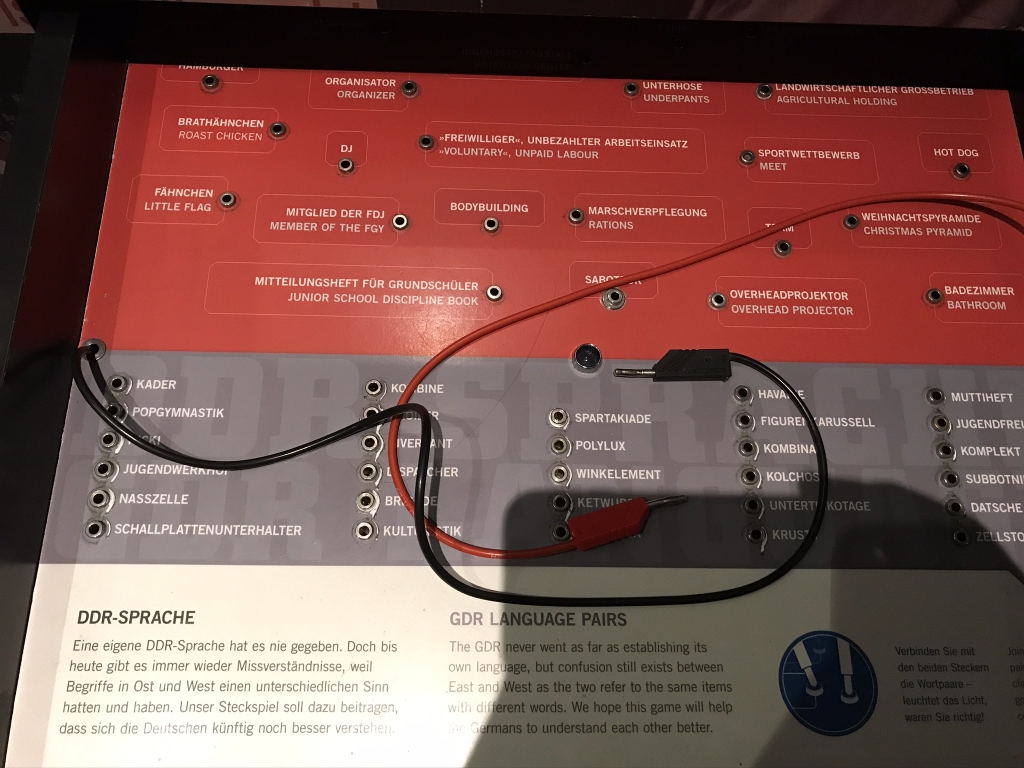

This was pretty interesting too. With a rarely-crossed, opaque border between them, the two Germanies' languages diverged somewhat, with each country coining its own terms to describe the same things (again, just like the two Koreas). Here you're supposed to put the red prong in a hole on the red Western side, the black prong in a hole on the gray Eastern side, and if those two terms mean the same thing, the little light in the middle comes on. I couldn't do much more than guess, though I did correctly surmise that "Ketwurst" (fourth from the top in the center gray column) meant "Hot Dog," mostly just because it ended in "wurst."

The Stasi--Staat Sicherheit meaning State Security--were East Germany's equivalent of the KGB and were most infamous for bugging people's apartments and tapping their phones. This is a reconstruction of a typical agent's workplace. Pick up the phone on the left and you can listen to people having conversations. The portrait over the desk is of Erich Honecker, who as General Secretary of the SED was East Germany's head of government for most of the last half of its existence.

A large portion of the museum was a full reconstruction of a typical East German apartment. This is the master bedroom. Over on the left you can see some typical East German clothes hanging on a rack. You can hold those up in front of yourself as you stand in the mirror, and see what you look like in them. That sign on the wall on the right mentions some interesting facts: "East Germans had sex earlier, married younger, had more children and were more likely to have an affair or to divorce. Was this due to the greater levels of female employment, the positive effects of social solidarity or just because there was generally less to do under Socialism?"

This would be the kids' room.

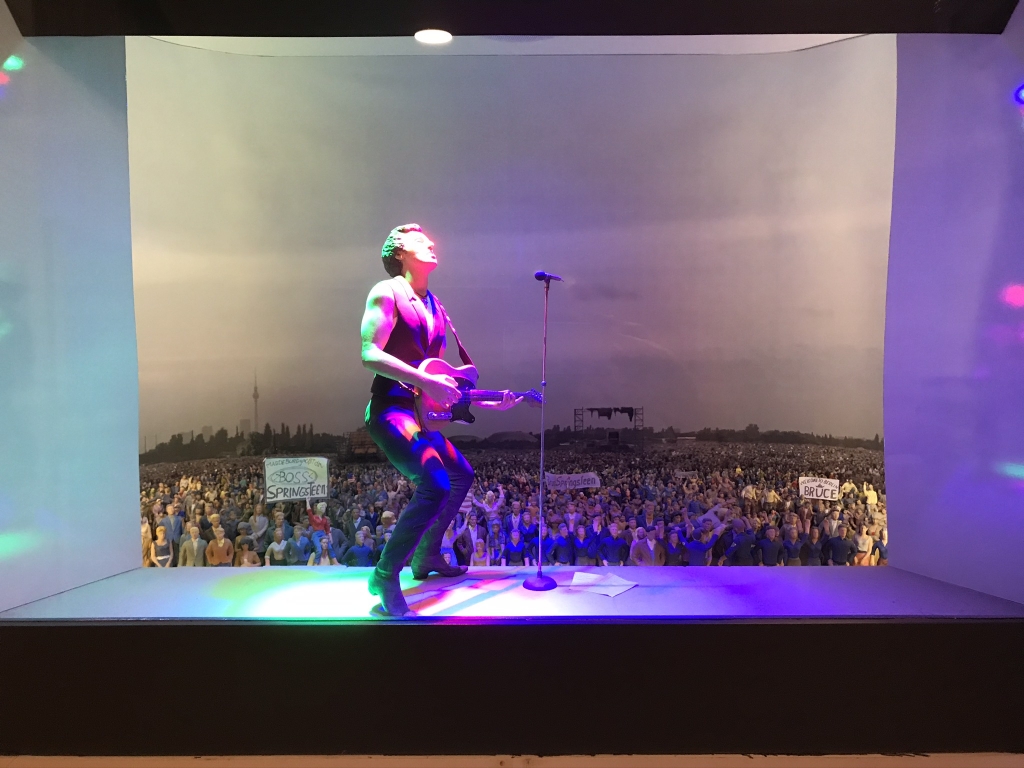

Open up a cabinet in the kids' room and you see this diorama of a Bruce Springsteen concert, which happened on July 19, 1988 in East Berlin. The SED had organized this concert because they feared the youth of the nation were turning against them, but their plans backfired because seeing this show just made the people want to knock the wall down even more.

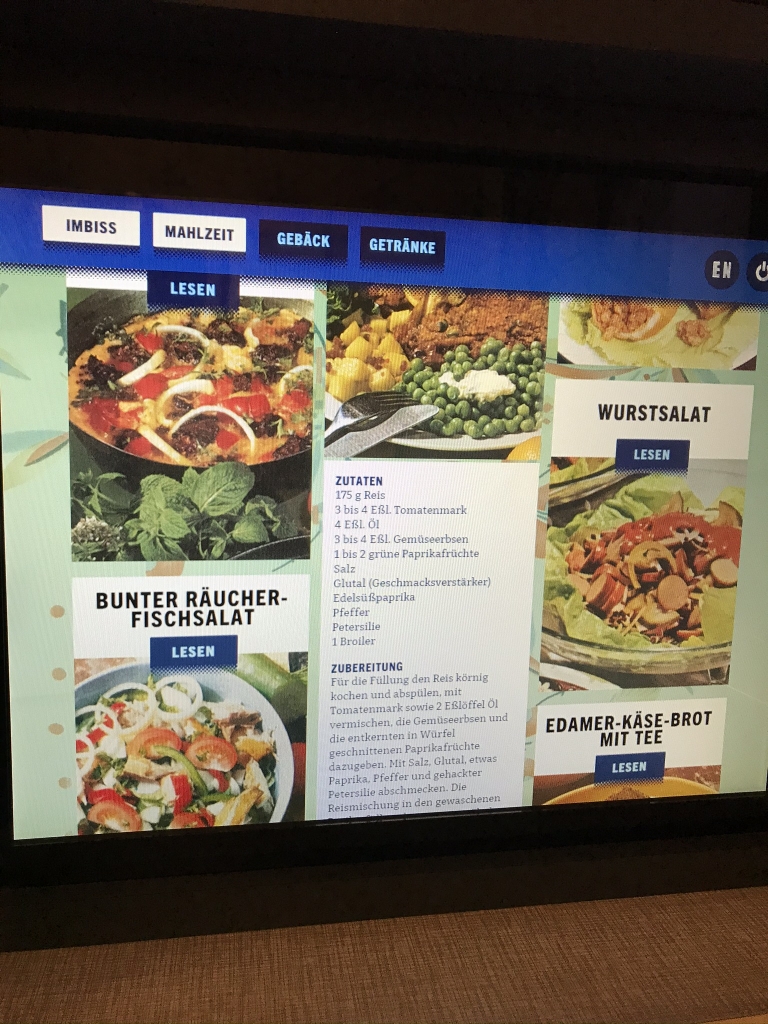

This display is in the kitchen, in which you can look at all these different dishes that were commonly eaten in East Germany. And not only that, if you see something you like, you can print the recipe! And that's just what I did for three of them: Hungarian fish soup, pumpkin kraut, and Tilburger-style rabbit. Since rabbit meat is likely hard to come by, I may have to substitute something else in that one. (I didn't know Kaninchen meant "rabbit" when I printed it)

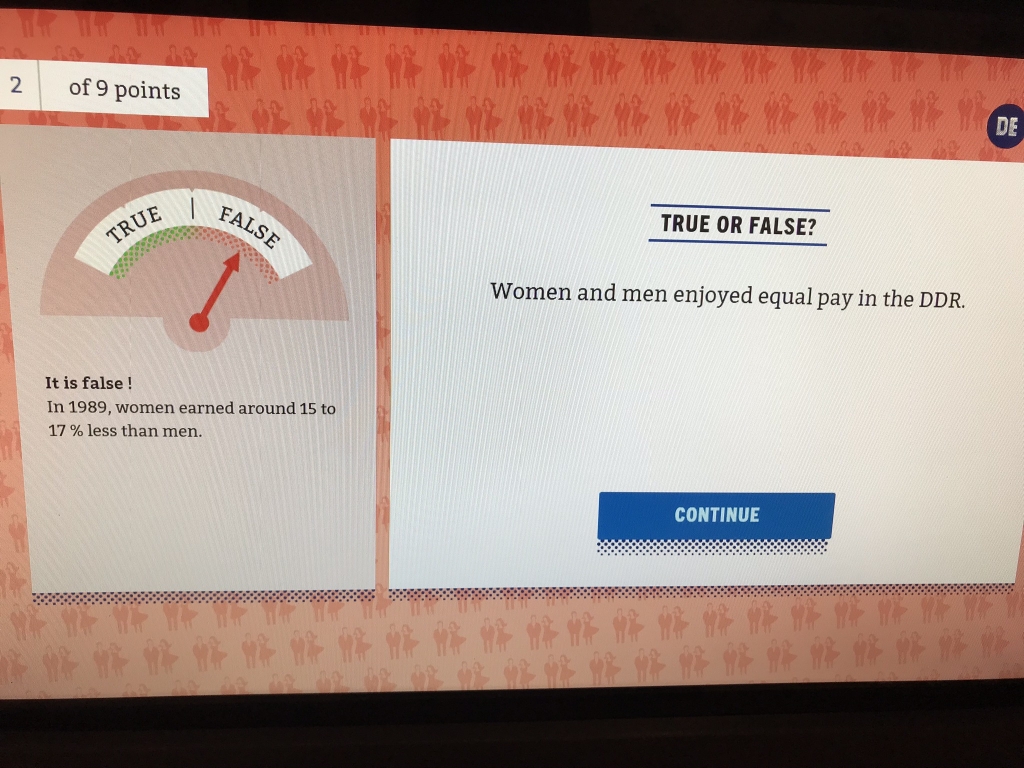

This trivia game was also in the kitchen. The East German government talked a good game about gender equality, but reality did not live up to their promises. Women in East Germany earned less money than men doing the same job, they did more housework, and while there were women in politics, none of them ever made it as far as the Politburo.

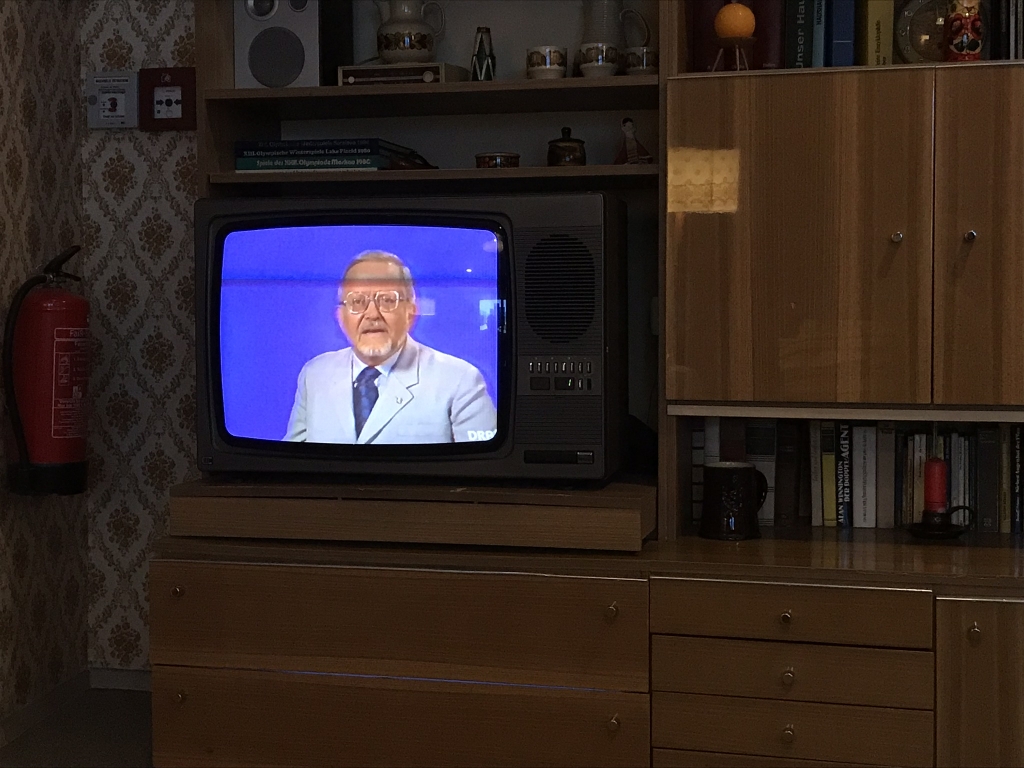

Now let's go into the living room. Want to watch some authentic East German TV programs?

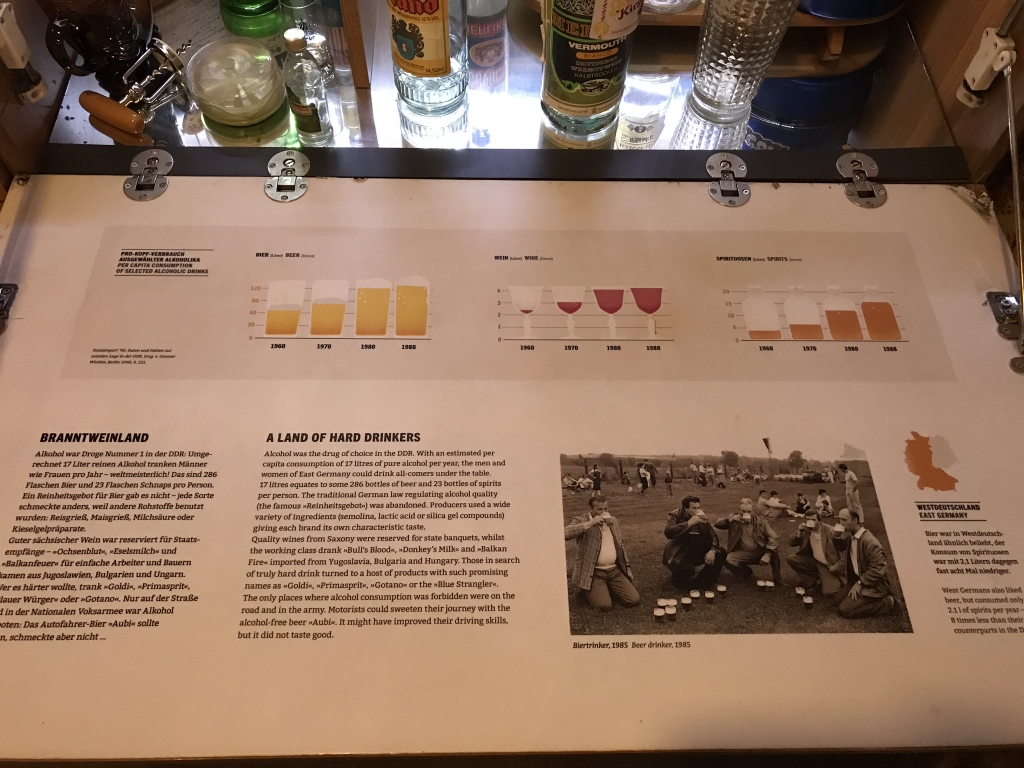

But first let's go to the mini-bar and pour ourselves some stiff drinks. East Germans were hard drinkers.

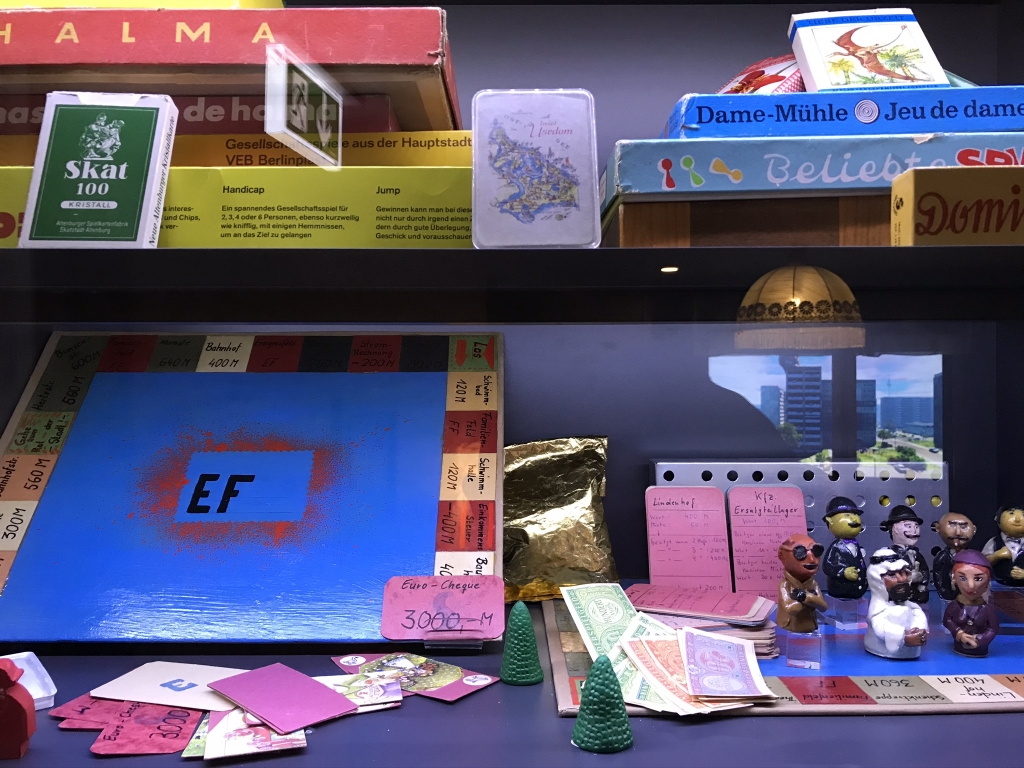

Or maybe we'd like to play some homemade board games?

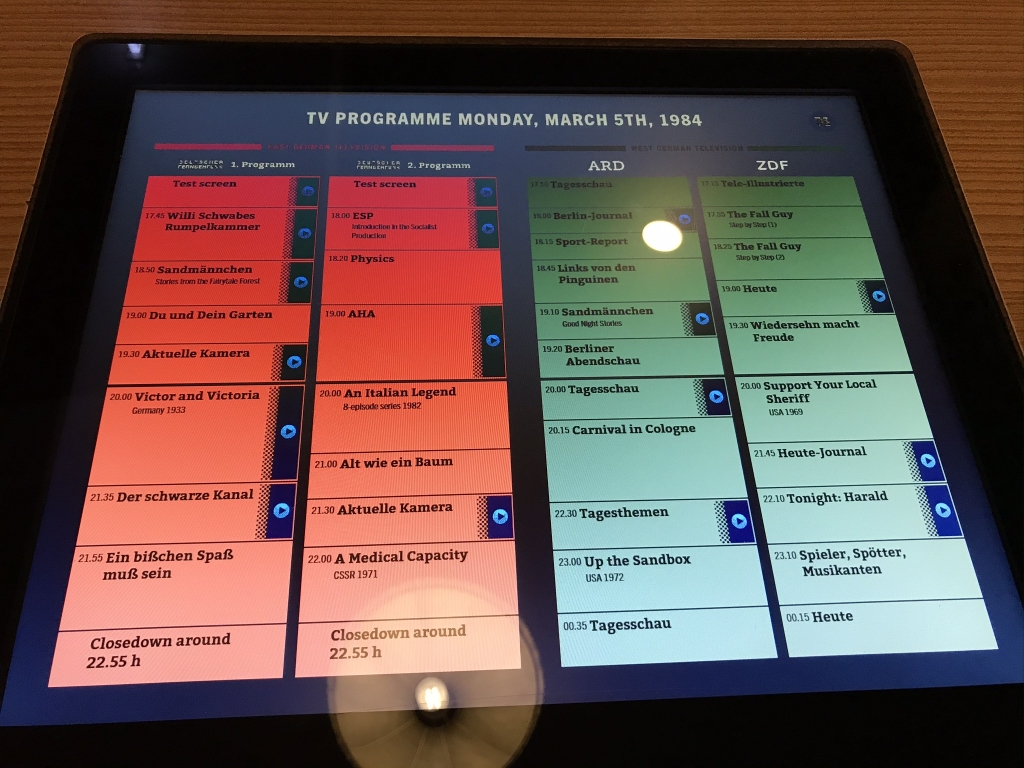

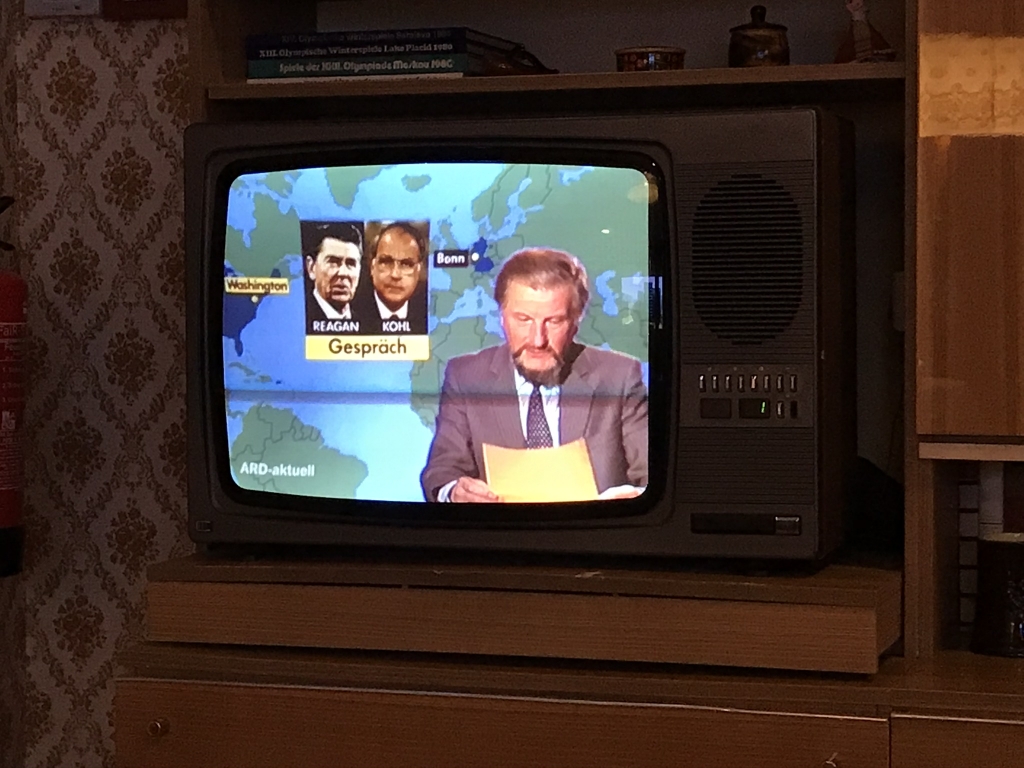

OK, so what's on the TV? The two red columns on the left are the schedule for East German channels, while the two green columns on the right are for West German channels. If there's a "play" button, you can watch a clip. TV sets in East Germany could easily pick up West German broadcasts, and most everyone watched them, but they couldn't openly talk about it because it wasn't exactly an activity they wanted the authorities to know about. Notice how both East and West had a show called Sandmännchen? Those were two different kids' shows, one Eastern and the other Western, which just happened to have the same name ("Little Sandman"). The guidebook I bought said that school teachers, all working for the state, would often innocently ask the kids in their classes about what they saw on Sandmännchen last night, as a way of sniffing out what families were watching the wrong TV stations.

This is a clip from Der Schwarze Kanal ("The Black Channel"). The authorities couldn't do anything to stop people from watching West German news broadcasts, so the best they could do was make this propaganda program, in which a commentator discusses what the Western news shows are saying, and telling you why it's false and what the real "truth" is. The museum guidebook I bought says "His message was simple: West Germany was still run by the Nazis."

This is one of those West German news programs, Tagesschau, which is still on the air today, that East Germans watched all the time but couldn't openly admit to it.

30 years after reunification, it's still not all sunshine and roses. The former East is still economically depressed compared to the former West, with workers earning lower wages than their counterparts in the former West. Easterners who move to Western cities for work often find themselves discriminated against by Westerners who consider them backwards hicks.

Many Easterners feel like their former country's legacy is being erased and there is also a lot of "Ostalgie," that is, nostalgia for the East (Ost) manifested in Communist-themed souvenirs and in films like Good-bye, Lenin!

A couple years earlier when I was a newcomer in Stuttgart, I once went to a German language class because I thought it might help me practice my what is my third language. It was far too basic and below my skill level, though, aimed at rank beginners, which is why I never went back, but there is something I will never forget. The teacher we had showed us a map of Germany and referenced the 2016 US election that was still fresh in our minds. "You have states like Ohio and West Virginia where there are many people who feel like they have been left behind by the modern world." She gestured at what used to be East Germany and said "Here it's the same, there aren't enough jobs, people feel left behind. Many people don't speak English, which is something you need in today's world. Many of them do speak Russian, which is not something you need today." She went on to explain that the former East is where the far-right anti-immigrant AfD party gets most of its support.

Germany may have officially reunited 30 years ago, but that erstwhile border still exists in everyone's minds.