After my all-too-short taste of Savannah, I was on my way to another, similar Old South city: Charleston, South Carolina. The two whole days I spent there were the best part of this whole week.

Wednesday, November 3, 2021

Amtrak's northbound Palmetto began its daily journey in Savannah at 8:20am. The trip lasted about an hour and a half. Like the last train ride I took two days earlier, there were quite a lot of passengers on the train. During the ride I finally finished off Benjamin Franklin: An American Life which I had started two months earlier.

I might add that this train ride was free of charge for me. During the summer when I spent two months in Maryland, I racked up enough Amtrak reward points on my trips to NYC and Philadelphia that I'd earned a free ride, which I redeemed on this trip from Savannah to Charleston.

Amtrak doesn't actually have a station in Charleston. The core of the city is built on the tip of a peninsula which is surrounded on both sides by several swampy islands which are separated from the mainland, and each other, by a twisty maze of rivers. That's not exactly conducive to building a rail line, so the tracks that run along the coast are, in this area, a few miles inland. So the nearest station to Charleston is actually in a suburb, North Charleston. Back in the old "golden age" of American railroads, one could have boarded a regional train at that station and ridden it directly into the middle of downtown Charleston; that service has long since been shut down, so now to get from the North Charleston station into downtown Charleston, I had to use a local bus. Two, actually; I had to ride 104 from the station to an intersection not too far away, and then transfer to 10 which goes into the heart of downtown. Because of the transfer, the total fare was $3.00.

I stepped off bus 10 some time later when I realized it had entered the city center. Soon I was walking down downtown's main thoroughfare, King Street.

King Street really reminded me of Königstraße in Stuttgart, the German city I'd lived in for two years, and not just because of the name (Königstraße means "King Street"). This is the main drag which is lined with shopping and restaurants all the way down. The biggest difference is that cars drive on King Street while Königstraße is pedestrians only.

From here I walked to the Airbnb house, which was easy to get to. Charleston, at least the center of it, is just as walkable as Savannah, with endless shops, cafés, restaurants, parks, and stores all easily reachable on foot from the houses and apartments, or from either of the two universities on the peninsula. This is the kind of city I love.

After checking in at the Airbnb house and leaving my luggage behind, I needed to find someplace to eat for lunch. This, of course, was easy, because in a city as well-planned as this all I had to do was walk in the general direction of downtown and pick any place that stood out to me as I passed by. What stood out to me was Fuel Cantina. This place was built in a former gas station which was probably built in the '50s, judging by the building style. I'd recommend this restaurant; it's at the corner of Rutledge and Cannon. For lunch I had a grilled shrimp salad, and I accompanied that with two beers they had on tap: John Paul Jones red ale, made by the Plankowner brewery, and 32°/50° Kölsch made by COAST.

Even better, people behind the bar recognized the Hulaween wristband I was still wearing! They had wanted to go to it but couldn't.

Another cool place to check out if you want coffee is Tricera Café near the King and George intersection. Since it's right next to the College of Charleston, it definitely has a college town feel to it.

I had wanted to swim some laps at local pools at least once during my week-long tour, and right now I had time for that. The MLK Pool looked like a great place to do that, and like anywhere else in the middle of Charleston I easily walked there. I really liked the MLK Pool. It's the only pool I've ever swam in on this side of the world that was 50 meters long. Back in Germany I usually did my laps in 50m pools, but in the States every public pool I've ever been to was either 25m or 25 yards.

The rest of Wednesday evening was devoted to eating and drinking. All the tourist stuff would have to wait till Thursday.

What to do for dinner? One of my South Carolina friends who I had been camping with at Hulaween recommended a place called Juanita Greenberg's. This restaurant/bar is right where it can be easily found on King Street. It's almost but not really a Mexican restaurant. Google Maps, I notice, describes it as "Mexican-inspired." The food was pretty good; I had a "Mexican Salad with Fish" which was a salad with black beans, Jack cheese, and flounder. To drink I had a beer I'd recommend, Holy Citi Pilsner.

Now for some bar hopping on King Street. The first place I found was a kind of place I rarely visit or even find, a wine bar. This one was named Stars and they actually had wine on tap. That is, a row of taps on the wall behind the bar, which looked like beer taps but dispensed wine. I'd never been anywhere like this before. First, from the taps on the wall, I had a 7oz glass of Malbec. That was a pretty good red wine, although I'm not into wine that much so I can't really judge it. They also had beer there, so I had a Birdsong Lazy Brown Ale, which was made by a brewery up in Charlotte, North Carolina where I'd be visiting the next day.

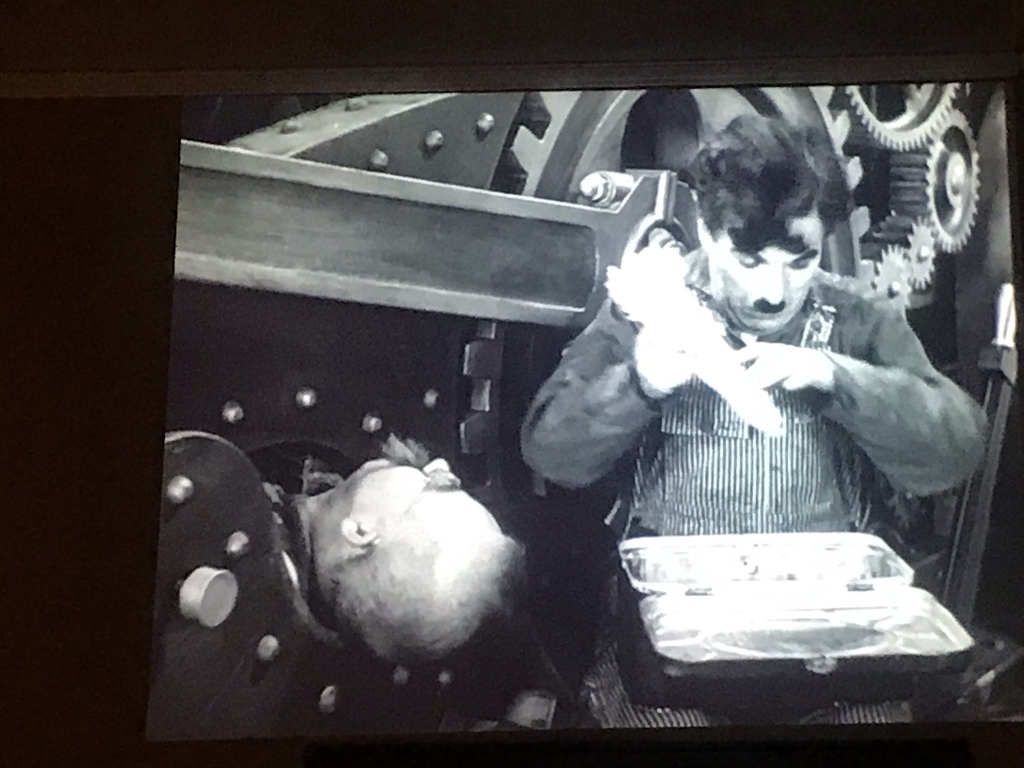

After Stars, I walked down the street to another establishment, Belmont. This place had a real retro theme to it, looking like something out of the 1930s or so. There was even a huge screen on one wall showing a Charlie Chaplin movie...

I think this was Modern Times.

They had a few unique mixed drinks on the menu at Belmont. I noticed one called Monk's Cafe, since that was an obvious Seinfeld reference. This particular hot coffee-based drink contained a rum blend, espresso, and cream. I'd have another if I came back, although it tasted a lot like molasses. After that I had an Irish Coffee, and since that was enough caffeine and alcohol for one night, I started the walk back to the Airbnb house after that.

Thursday, November 4, 2021

This trip sure had lasted awhile by this point. It was a whole week before that I had boarded a Greyhound bus in Atlanta bound for north Florida, on the way to Hulaween. And now, seven days later, after that amazing music festival, an all-too-brief tour of Savannah, and a half-day in Charleston, I'd be diving into some museums and a historical tour of Charleston. Since Wednesday had mostly been familiarization with the city and bar-hopping, Thursday was going to be devoted to museums and a bus tour.

After a shower at the house and breakfast from somewhere nearby, I walked down to the Tricera Café to start waking up with an oat milk latte.

Hanging on the wall at Tricera. If we ever find a real Triceratops in our time period, here's what we'd call the different cuts of meat.

Now I continued my walk southeast, in the general direction of the southern tip of the peninsula. This was rather scenic.

Here are two historic churches I passed by the day before, and happened upon again now. The white church in the back is St. John's Lutheran Church, built around 1816-1818. The sand-colored church in the front is the Unitarian Church in Charleston, built in 1778, the oldest Unitarian church in the South and the second-oldest church building in Charleston.

Charleston is full of historic churches, which some suspect may be the origin of the city's nickname, "the Holy City." Many of these old churches, like the ones in the photo above, are painted with a single solid pastel color.

This is a house I passed by and it's pretty typical of the Charleston style. Some houses are smaller with one story, others are bigger like this, but they all have one thing in common. On the right of the photo you see the front of the house, and there's a door that appears to be the front door. But that's not really the front door, as you can see, it merely leads to the piazza--what Charlestonians call a porch--on the side of the house. I've never seen homes designed like this anywhere else in the world, only here in Charleston. And it's not in the whole city, only in the historic core here on the peninsula.

Another historic church, St. Michael's Anglican Church.

Eventually I made it to the waterfront along the southeastern shore.

In that strip of marshy grass along the shore in the foreground, you can see a glimpse of what the local terrain looks like outside of the city. This low-lying area was long a center of rice cultivation. Off in the distance you can see the Arthur Ravenel, Jr. bridge which spans the Cooper River, connecting the old city center with more recently-developed neighborhoods on the other side.

Around this area of the old city I stopped at another great café, Bakehouse, for an Americano and a piece of coffee cake.

Now, after that picturesque walk through the city center, it's time to take a deep dive into four centuries of history. Just a few steps south of Bakehouse on East Bay Street, I found my first destination of the day: the Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon. This was built by the colonial government between 1767 and 1771 and was used for a variety of purposes. It was a custom house, city hall, public market, and a prison, among other things. Now it's a museum, owned by the Daughters of the American Revolution. It has two above-ground stories and a basement.

The first and second floors are places where you can just walk through at your own pace. The displays here have a great deal to say about the history of this building, Charleston, and South Carolina, and their roles in the transatlantic slave trade, the golden age of piracy, and the Revoutionary and Civil Wars. With regard to the slave trade, it was the city's whole reason for being for the first century and a half of its existence; it's estimated that over half of all the Africans who were brought to North America in chains first arrived on this continent in Charleston, or Charles Town as it was called before the Revolution. On a spot outside the Exchange, even before the building was built, was the site of numerous slave auctions. Charles Town was also raided by none other than the pirate Blackbeard in 1718, and in that same year was the place where another notorious pirate, Stede Bonnet, was tried and hanged. The Exchange building itself was where, in 1788, a state convention debated whether to ratify the new United States Constitution.

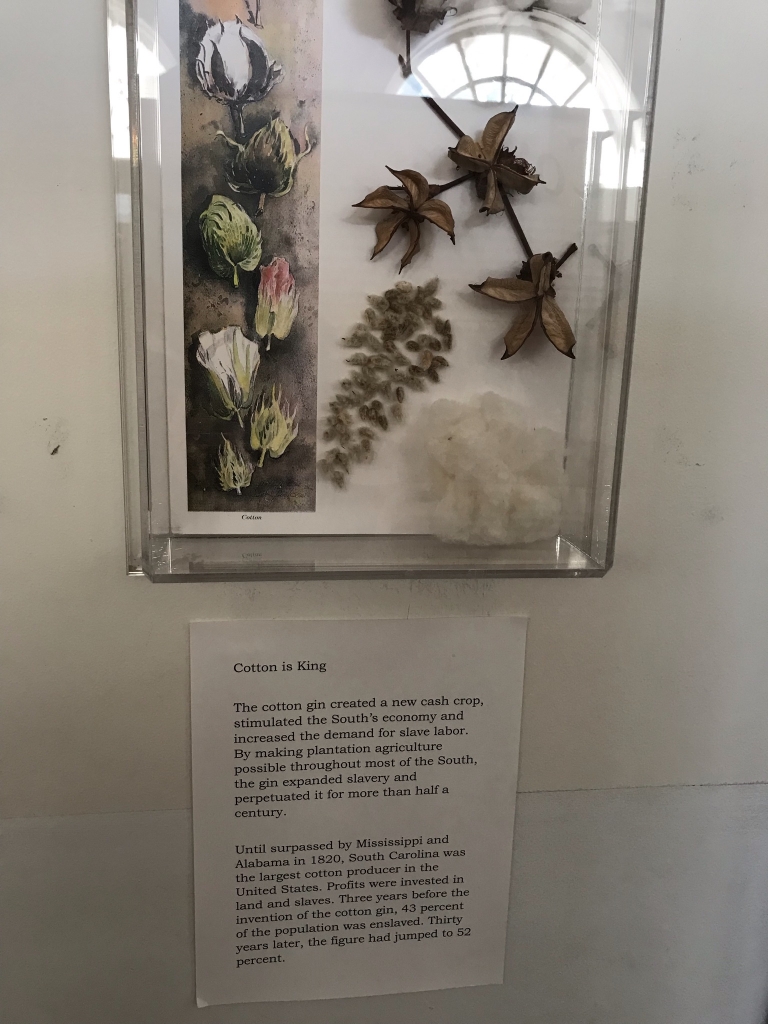

While South Carolina was mostly known for its famous rice, cotton eventually eclipsed it and all other crops throughout the southern states after the famed inventor Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin. Cotton farming used to be unprofitable due to the labor-intensive process of removing the seeds from the fibers, until the cotton gin--gin being period slang for engine--made removing the seeds fabulously easy. This had the tragic side effect of perpetuating slavery as cotton production exploded throughout the south. As another sign in the museum said: "Within twenty years of the invention of the cotton gin, the number of slave owning families increased from 25 to 40 percent."

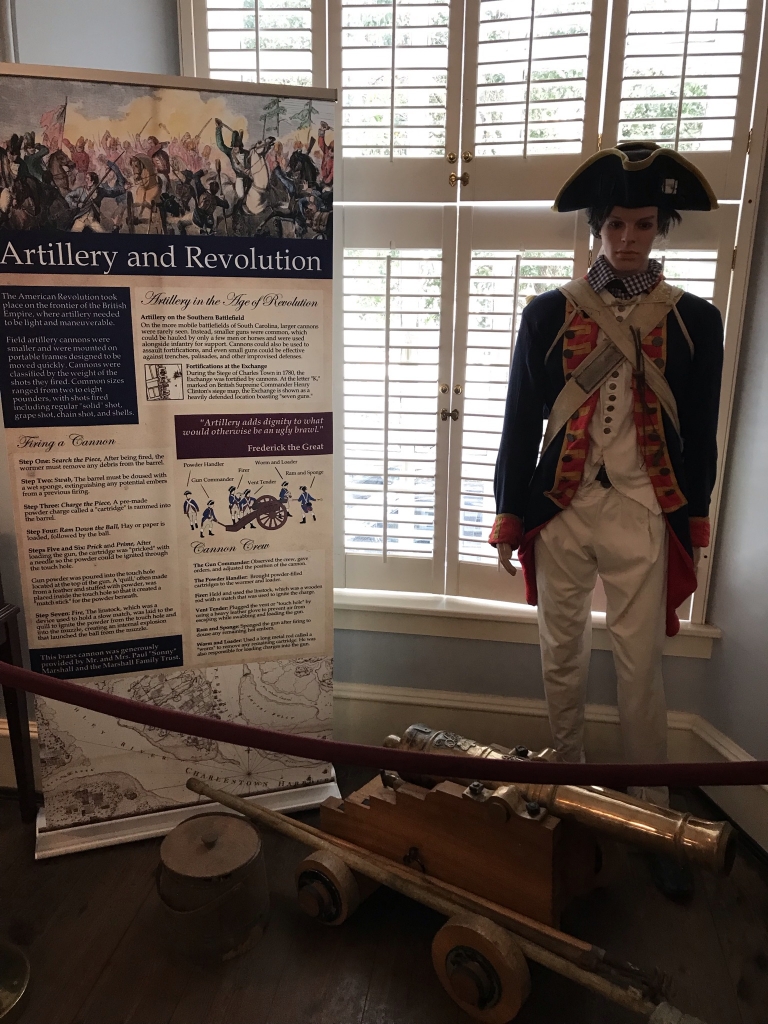

Everything you ever wanted to know about firing a cannon during the Revolutionary War.

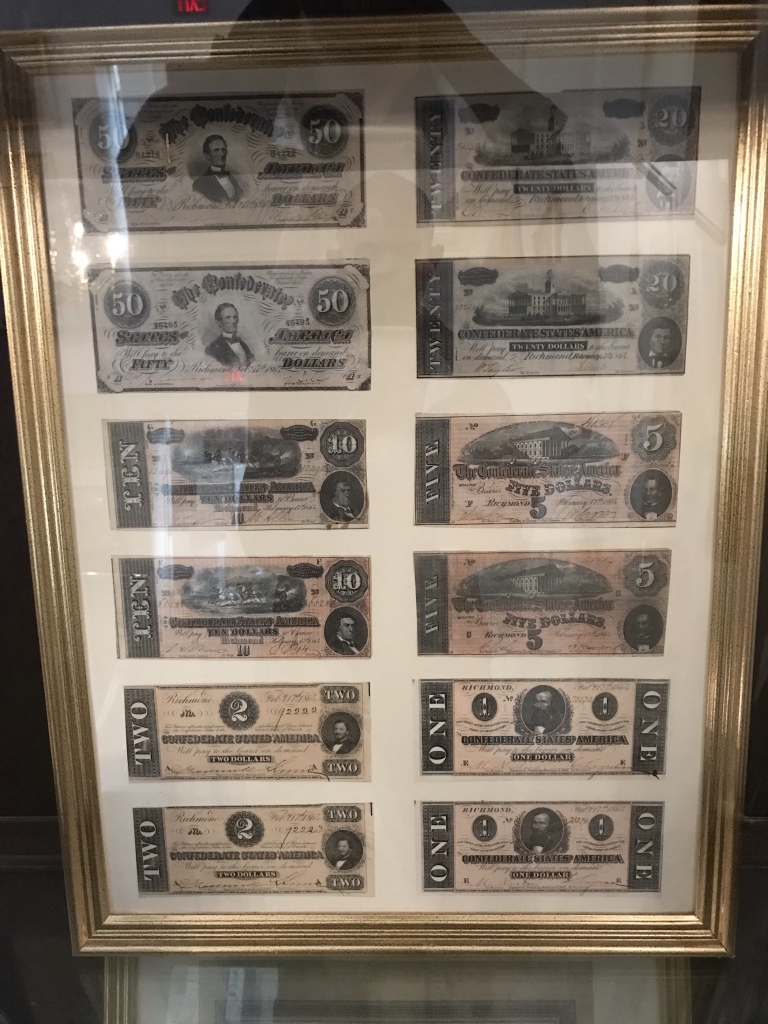

Confederate money of every denomination, printed in 1864.

The basement of the Old Exchange building is the Provost Dungeon. Unlike the above-ground floors, in this one is a guided tour where a docent walks you through the space and discusses the history.

The basement was used as a prison during the 1780-1782 British occupation of Charleston. If you're wondering why it's called "Provost" when you've likely only ever seen that word used as a title for an official at a university, it's because the word was derived from a Latin word meaning "overseer."

Remains of the Half-Moon Battery, a fortification dating from 1698.

The people languishing in the Provost were thrown in there for a variety of reasons. Some were common criminals, some were insubordinate British soldiers, some were escaped slaves. Everyone, regardless of race, gender, or offense was locked up in the same space, making the dismal Provost a rare place in colonial Charles Town where there was any kind of equality.

After the Old Exchange, it was time for lunch. On Broad Street I found a great place called Brown Dog Deli, where I could eat a chicken shawarma wrap. That's definitely a place I'll recommend.

Next stop: a bus tour I'd registered for, Gullah Tours. This is a long-running bus tour which focuses on the Black history of this city which was majority-Black for almost all its history until the 1980s. As its name suggests, it also has a focus on the Gullah language, the English-based creole language traditionally spoken by the Black residents of the South Carolina and Georgia coastline. The founder, tour guide, and bus driver Alphonso Brown has been doing this since the early 1990s.

Gullah, also known as Geechee, originated in the horrors of slavery. Those people who were brought here as slaves came from all over west Africa and since they didn't have a common language between them, one naturally sprung up. It is based on English--that is, the English spoken by colonial and antebellum-era Southern planters--with a simplified English grammar and mostly English vocabulary, with many loan words and grammatical constructions borrowed from various west African and European languages. For most of its history, no one, not even the people who spoke it natively, considered it a language of its own, and only thought of it as a debased form of English. It wasn't until 1929 when Lorenzo Dow Turner, a linguist at the historically-Black Howard University in Washington, DC, began interviewing and recording Gullah speakers in South Carolina's and Georgia's coastal regions. He later traveled to Sierra Leone in west Africa and further traced its origins.

As Alphonso put it, "Bad English is bad English, Gullah is Gullah."

This house at 67 Alexander Street was built by Richard Edward Dereef, a wealthy free Black man in the antebellum days, in April 1838 to be rented out to tenants. Like so many other homes in the city, the piazza (porch) is on the side of the house; that front door you see doesn't actually enter the house but leads to the piazza. This was supposed to maximize ventilation during the hot summers.

A recurring theme during this tour was the artisanal ironwork that featured in many gates and fences all around old Charleston. It was all the work of Philip Simmons, a Black blacksmith who was known for his intricate, decorative designs which grace historic buildings throughout the center of the city. He died in 2009, but not before passing his craft on to apprentices. At one point in the tour we stopped and got out of the bus to see one of his successors fashioning new creations at his blacksmith shop.

Philip Simmons designed the "Heart Gates" for the church of which he was a member, Saint John's Reformed Episcopal, in 1998.

This is Philip Simmons' "Snake Gate." He made it in 1961 for the Gadsden House at 329 East Bay Street, the house built in 1800 by Christopher Gadsden who designed the famous "Dont Tread On Me" flag.

In the middle of the tour we got a short lesson on how to pronounce certain street names in Charleston. Legare is pronounced "le-GREE"; it rhymes with degree and agree. Barre sounds like the name Barry while Hasell sounds just like hazel. That last one, Huger, was slightly controversial; it's either "YOU-jee" or "HEW-jee" but the people on the bus who were from South Carolina couldn't agree which one was right. Many of these names have a French origin, probably coming from the Huguenots--French Calvinists fleeing persecution in their Catholic homeland--who settled in the city during colonial times. After three centuries their pronunciations have been mangled to the extreme.

You can find a comprehensive pronunciation guide here. There's also Prioleau ("PRAY-lo"), Beaufain ("BYOU-fane"), and many more head-scratchers. According to that list, the H in Huger is silent.

Interestingly, while walking down King Street later that day, I overheard a pedicab driver--yes, Charleston has pedicabs just like Austin--talking on his phone saying he had to pick up someone on "Hassle" Street. Sounds like he's not from around here...

At another point on the tour, we stopped at the cemetery at Old Bethel Methodist Church, a graveyard for Black Charlestonians, enslaved and free. Alphonso pointed out a curious feature of many of the headstones: they had a symbol on them depicting a hand with its index finger pointing upward. He asked if anyone could guess what that might mean, and no one had any idea. It's supposed that the finger symbol is actually a secret Islamic reference. West Africa had been largely converted to Islam during the Middle Ages, and thus the Africans who were forced across the ocean centuries later were mostly Muslim before being coerced into Christianity on our shores. The one finger pointing up is believed to be an affirmation of belief in the oneness of God, denying the Christian concept of the trinity. If that's true, it would mean that some generations of African Americans maintained their ancestral religion in the face of forced conversions.

Alphonso also said that the crescent moon in the South Carolina flag was originally meant to be the Islamic crescent moon symbol, but I'm not sure I buy that.

Emanuel AME (African Methodist Episcopal) Church, better known as "Mother Emanuel," is the oldest AME congregation in Charleston. The AME denomination started in Philadelphia in 1787 when Black Methodists weren't accepted in white Methodist churches or were heavily discriminated against. The first Emanuel AME Church was built in 1818, but it was burned down in 1822 by a white mob because one of its founders, a free Black man named Denmark Vesey, had been part of a plot to start a slave revolt. The current building went up in 1891. Today it's sadly most recognizable for the mass shooting that happened here in 2015 which left nine dead.

Mother Emanuel is on Calhoun Street, which was named after John C. Calhoun, the antebellum Senator from South Carolina who had also been Vice President of the US under Andrew Jackson, and was an ardent defender of slavery and a passionate advocate of southern secession. "He was no friend to Black people," Alphonso said. For that reason, generations of Black Charlestonians have pronounced his name "Killhoun."

I don't want to go on too long about the tour. All I'll say now before moving on is that I totally recommend it. If you're in Charleston for only a short time and can only do one bus tour, do this one.

At the office where the tour began and ended, there was a gift shop. I bought a small bag of grits which I brought home and found pretty delicious with the right spices. I also bought Alphonso's book A Gullah Guide to Charleston which is a great companion to the tour I just did. This book describes many noteworthy sites around the city which are important in Black history, including everywhere the tour bus stopped, and it's all bilingual in Gullah and English. Here's an example, dealing with the next place I visited that day, the Aiken-Rhett House:

Gham by 'e pah wen 'dead, Gub'nuh Aiken open up 'e house yuh plenny uh time fuh mek um big'uh. Dem slabe shanti still deh dey een de back yaa'd obbuh de haws' ban' 'n de kitch'n. Een no slabe bin lib yuh since aftuh de Whah when deh bin restruct'n we. Now de slabe hous' wah deh yuh now, duh cos' so much money dat dis dem million'nay people kin pay fuh lib' een burruh.

Inherited from his father in 1831, Governor William Aiken enlarged this house (originally built as a single house) several times to its present grandeur. In the backyard on one side are the original slaves' dwellings above the stable house and on the other side is the kitchen with six rooms of slave quarters upstairs. The slaves' quarters (often referred to as servants' quarters or dependencies) are the only known urban quarters that are still in their original and unlived-in state since Reconstruction. It is one ot the finest examples of slave urban living in the city. Many of the slave dwellings in the city are now private homes that sell from around $100,000 and up.

It was getting late in the afternoon and so there was only enough time for one more stop. Alphonso from the Gullah Tour had pointed out two places that were worthwhile, the Aiken-Rhett House and the Old Slave Mart. Both of these seemed interesting enough, but with only time for one, I went with the Aiken-Rhett House.

The Aiken-Rhett House, as seen from the Gullah Tours bus. From the outside you can tell it's a stately mansion but still mostly blends into its surroundings.

The house took me about a little more than an hour to go through. It's a self-guided walking tour, but they give you a device, it looked like a late-2000s iPhone or iPod Touch, and earbuds, with which you can read and listen to descriptions and anecdotes about what you're looking at as you walk through the house. Unlike most other historic buildings used as museums, the inside of the house isn't maintained in its pristine state, but has been left untouched and allowed to decay for a century, which also included some damage taken from Hurricane Hugo in 1989. This gave the whole house a rather eerie atmosphere.

The whole tour felt eerie to me for more than one reason. First, there's something about ruins that just fascinates me. For as far back as I can remember, I've occasionally had dreams about walking alone through crumbling, decaying buildings that seem to go on forever, and this was the first time I got to do this for real. This made my skin crawl but in a good way. But at the same time, there was the dark legacy of slavery that cast a shadow over the house, which manifested itself in the most subtle, innocuous ways you won't notice if it's not pointed out to you. I'll show you what I mean in the next few photos. This made my skin crawl in a bad way.

Like Alphonso wrote in his book, South Carolina's governor, William Aiken, inherited this house in 1831 and greatly expanded it in Greek Revival style. Aiken, despite being a slaveowner, was a staunch Unionist and opposed to secession. His daughter Henrietta, William's only child, married Andrew Burnett Rhett, a Confederate Army officer and the son of congressman Robert Barnwell Rhett, one of the fiercest advocates of secession in the South. We'll probably never know what kind of arguments that caused, but the wedding happened in 1862, giving the house the other half of its name.

This is what I meant about the dark legacy of slavery being manifested in subtle, innocuous ways. You see all those little hooks and nails all over the wall? They used to support an intricate system of cables which connected buttons throughout the house to bells. This was all a means for summoning slaves at the push of a button.

A place where lavish dinner parties once happened.

One of the few call buttons still left intact; most of the others have nothing left but a little stump sticking out of a hole in the wall. Seeing such a thing in every room, barely noticeable, is something that made this place feel creepy when you know what the purpose of it is.

Here's what a bathroom looked like before modern toilets and indoor plumbing were invented. That little seat on the right is the closest thing they had to a toilet back then. Without plumbing, it had to be emptied outside, and by now you've probably guessed whose job that was.

I'll definitely recommend the Aiken-Rhett House if you've got time for it. The untouched and unrestored interior really increased the feeling of walking through history.

Looking south while standing on Mary Street, between King and Meeting Streets. That building on the right sure looks like a train station...because it once was! Now home to the Charleston School of Law, 100 years ago it was a rail terminal. Back then, someone visiting from another city would probably have arrived in North Charleston, as I did, and then taken another train from there to this station.

The day's historical tours done, it was now late afternoon. While heading south for dinner, I stopped at a coffee house called Kudu, on Vanderhorst and King, for an Americano. This was a nice place with outdoor seating by a lawn.

This stretch of Bay Street is called Rainbow Row, after the varying colors of the houses. This really reminded me of Amsterdam.

I found a great seafood restaurant on the waterfront not too far from Rainbow Row, called Fleet Landing. Excellent place to get seafood, although if you want to sit at a table, you're probably in for a long wait, which is why I just took a seat at the bar. The food was great, and I had a delicious bowl of Lowcountry seafood gumbo. They also had some local beer on tap. I had a Lowtide Sweet Caroline, which was a Kölsch and I thought was not bad, and then an Island Coastal Lager which was OK but I didn't like as much as the Kölsch.

There's one more place I decided to check out that night, back on King Street away from the coast. It was called Pour Taproom and was a beer bar with an enormous selection of mostly local and regional craft brews.

All the taps looked like this, activated by touchscreens.

There were so many beers here from so many southeastern breweries that I'd never heard of. The first one I drank was actually an Oktoberfest Märzen, Commonhouse Aleworks Folksfest. The second and last...it was either a Straffe Hendrik Brugs Tripel from Belgium (not all the beers here were local) or a Liability Brewing Stainless Steel Magnolias lager. If you're a beer snob, you must visit Pour if you're ever in Charleston.

Friday, November 5, 2021

The visit to Charleston was almost over, with a bus taking me to Columbia at 10:30 that morning. All I had time to do was pack up and get breakfast and coffee from a café called 132 Spring, named for its address, and then walk to Meeting Street and catch northbound bus 10.

I think that CARTA, the local transit authority, could've planned the local bus routs a little better. It would make sense to have a single bus route connecting downtown Charleston with the Amtrak/Greyhound station. You can't just get on 10 and ride it to the station, you have to ride it almost there and then transfer to 104, a local looper in North Charleston which is the only bus that stops at the station. So that morning I had to step off of 10 at a gas station and watch time go by waiting for 104 to show up, which it didn't, so I had to call a Lyft to get me to the station where the bus to Columbia was waiting. The bus system is the only thing about Charleston that didn't impress me. I think if I lived there, I'd walk and bike to most places, drive my car to anywhere outside the peninsula, and only use the bus to get to the airport or train station.

Overall, I really loved Charleston, even more than Savannah. I've already gushed enough about how walkable both cities are, being designed for people before cars. And just like Savannah, there's a lot I missed out on. There were a few historical walking tours I wanted to do, including one focusing on the city's history with piracy. There's plenty more to see and do outside the city center, such as the Civil War submarine CSS H.L. Hunley. I will be back.