As a really accurate saying goes, "a language is a dialect with an army and a navy." Those of us on the west side of the Atlantic Ocean know there's a country called Germany, and another one called Austria and part of another called Switzerland, which speak a language called German. Turns out it's not that simple. German is the official language of all those countries, but every little region has its own language, which people usually refer to as a dialect, and is quite distinct from standard German. This is nothing like the situation in the US where people in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles have their own way of speaking English; it's more comparable to how people in Italy, Spain, and France have their own languages which are quite distinct from classical Latin. But those are all considered "languages" because Italy, Spain, and France each have an army and a navy, and their mother language Latin is totally dead.

The whole time I lived in Germany, I traveled all over the German-speaking countries taking pictures of any written examples of "dialects" I could find, which I shall present to you now. We'll start in the south, "high" up in the mountains and work our way "down" to the north.

Swiss German

Schweizerdeutsch is probably the most famous "dialect," although it's really more of a group of closely related dialects than a single one. Switzerland is known for having absolutely no stigma associated with speaking the local language; it's not considered lower-class at all. Every German-speaking Swiss person can speak standard German, but to them it's a second language they learned in school and only use on formal occasions (reading the TV news, church sermons, etc.) and in all written material.

Well, almost all written material...

A recycling bin at Basel's annual Herbstmesse (Fall Fair) which happens every November. The sign means "For a clean fair" which in standard German would be Für eine saubere Messe.

Outside a hair salon in Basel. The top says "Holidays are expensive" (Ferien sind teuer) and the bottom says "Come in and relax with us." (Komm rein und entspann dich bei uns)

An ad in a gondola at the Zermatt ski resort in Wallis canton. The word Gaudi means "fun" throughout the southern dialects. (Nothing to do with any Spanish architect) So I think this means "Whether with sun...or with snow...with Furri-Sepp fun is here!"

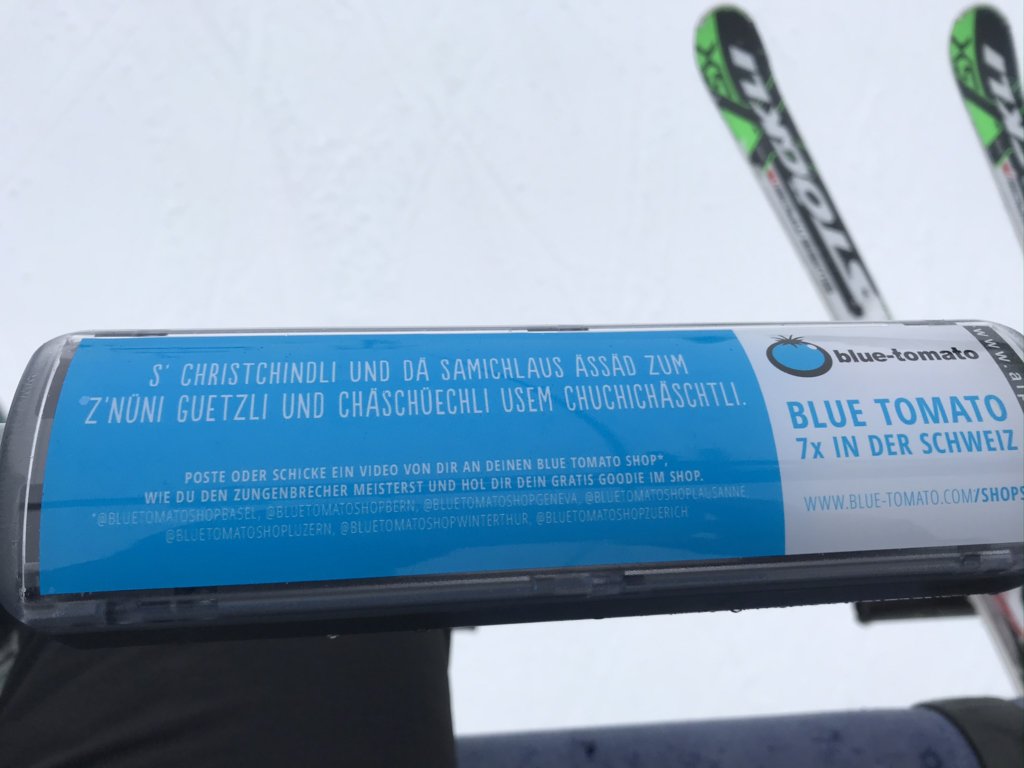

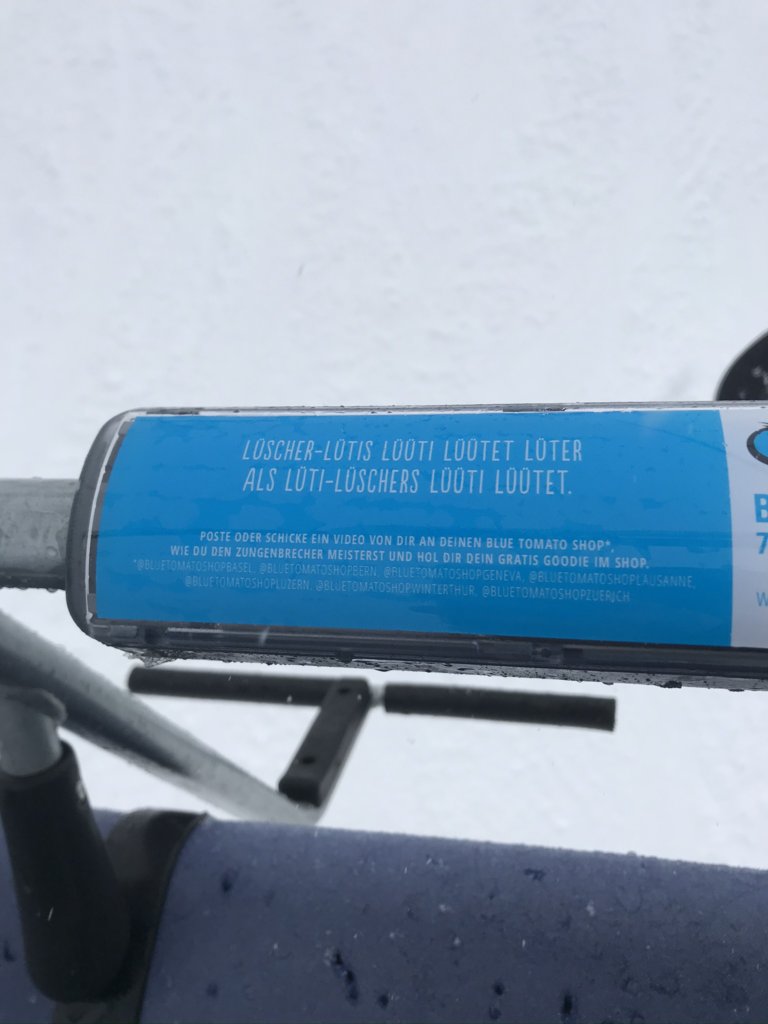

The next three I spotted at the Hoch-Ybrig ski resort in Schwyz canton. They're tongue twisters; the idea here is, you're supposed to make a video of yourself trying to say one, post it to Instagram while tagging Blue Tomato's various accounts, and you'll get some kind of prize if they like yours the most.

Knowing what little I know of the differences between Swiss and Standard, I'll take a crack at this. "The Christ child and Santa Claus ate for...[I have no idea]...and cheesecake out of the kitchen cabinet." This sentence shows off how Swiss often changes German k's into throaty ch sounds. That last word, Chuchichästli (Standard German Kuchenkasten), meaning "kitchen cabinet," is probably the most famous Swiss German word, because it shows so many Swiss peculiarities. Not just the replacing k's with ch's, but also the Swiss tendency to tack the diminutive suffix li (Standard lein or chen) onto nearly every noun.

All I can tell you here is that Lüüti means "people" (Standard German Leute).

Something or other about the Pope ordering ham and silverware? It's a tongue twister, it's not supposed to make sense.

The usual greeting in Switzerland is Grüezi. No one ever says Guten Tag in Switzerland, and if they did, they would pronounce it like Guete Tag.

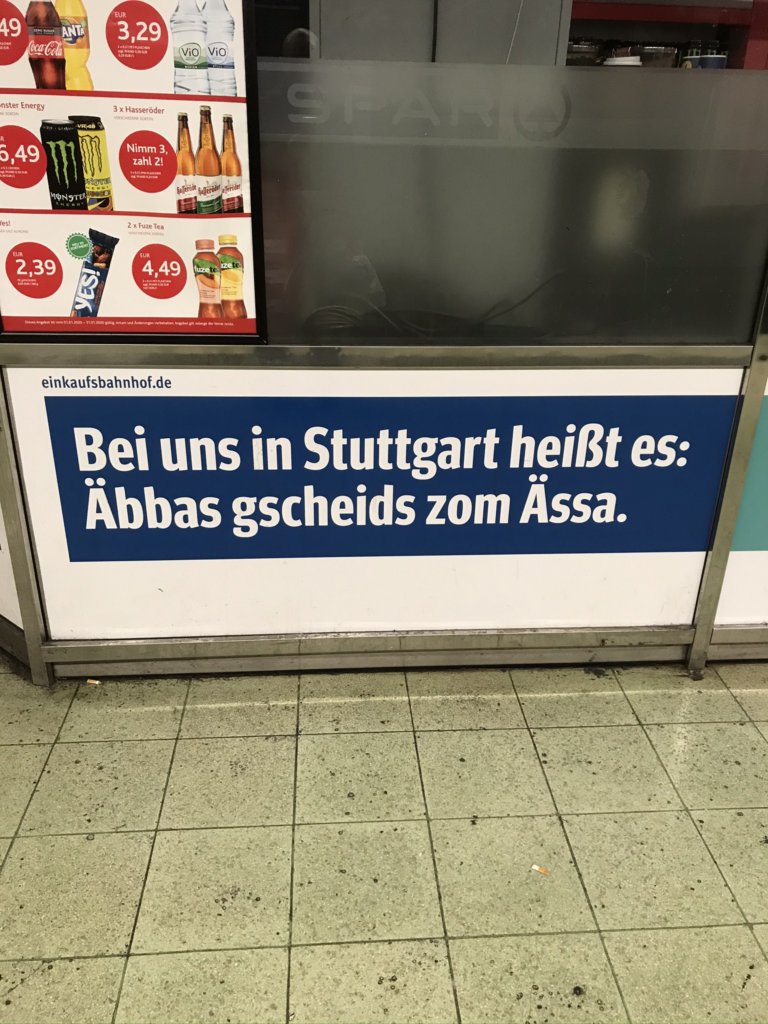

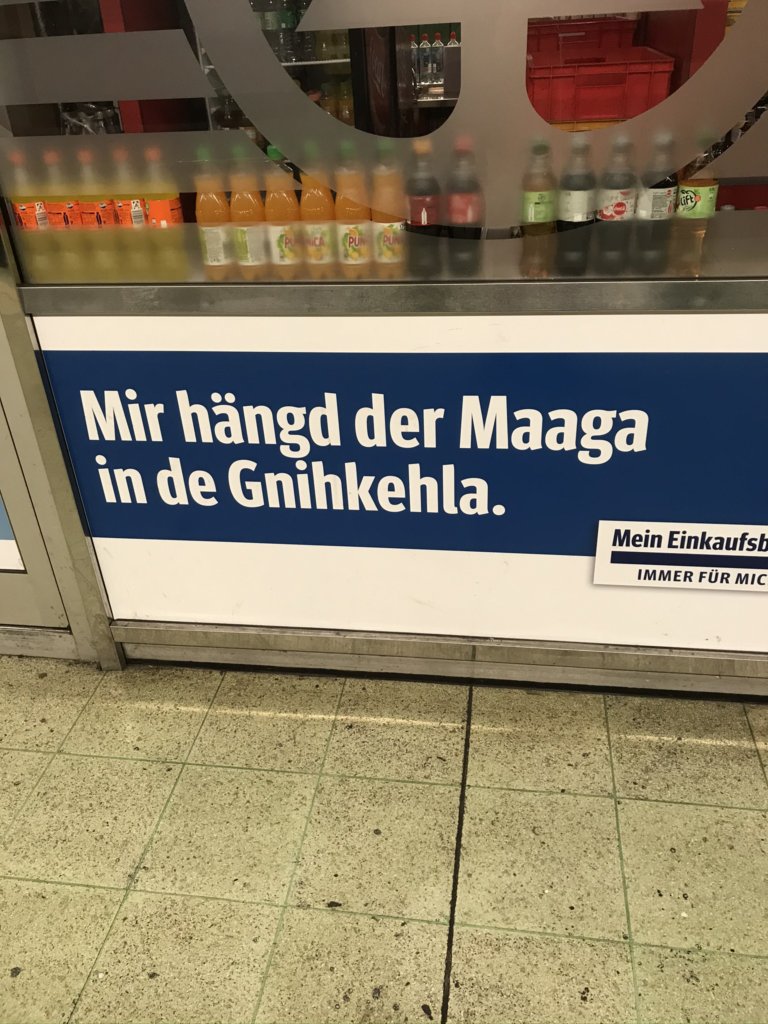

Swabian

Schwäbisch is spoken in the historic region of Swabia/Schwaben, which mostly lines up with today's state of Baden-Württemberg and a few places across the border in Bavaria. Stuttgart, Baden-Württemberg's capital, is called Schduagert.

You'll notice in a couple of these, they add le to the ends of nouns like the Swiss do with li. The Swabians like to call their state, Baden-Württemberg, s'Ländle, which in standard German is simply das Land ("the state").

An ad at Stuttgart's main train station. Just what is a Gnihkehla, anyway? A fridge? It seems "we're" hanging something in it.

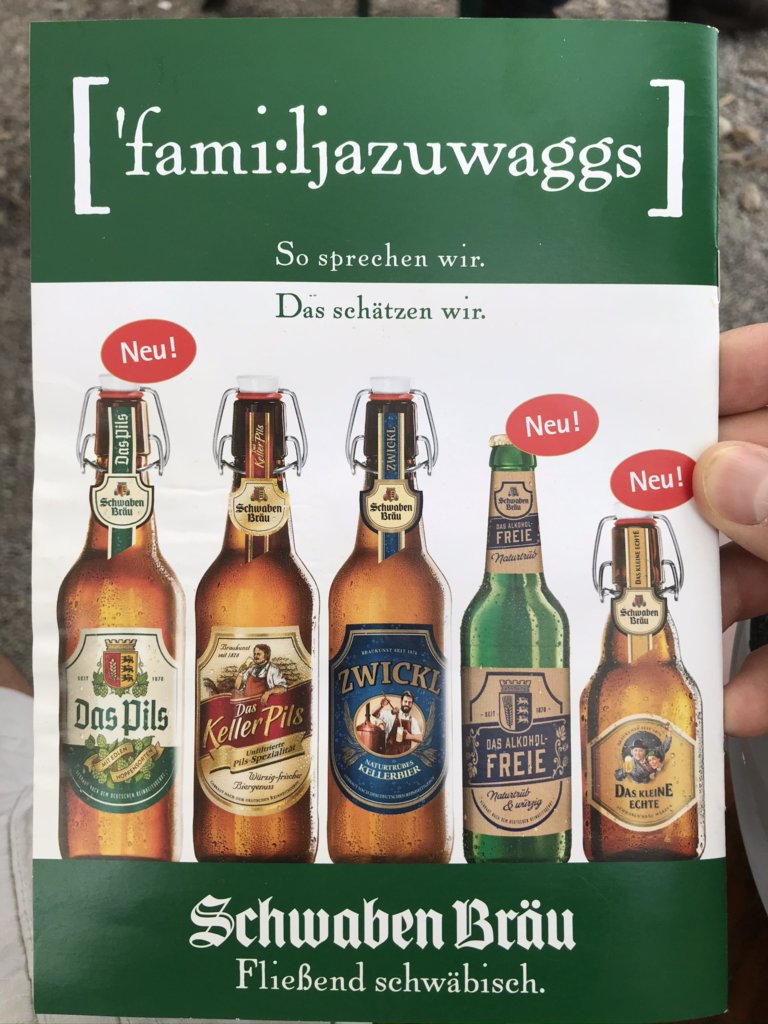

The next examples are from ads and packaging for Schwaben Bräu, one of Stuttgart's macrobreweries, for which Schwäbisch phrases are part of its branding.

"Genuinely the best" (Standard German Echt das Beste)

"[something] sought" I tried looking up various guesses at what I thought could be the standard German version of the first word on Google Translate and nothing worked.

The first is "Simply strong" (Einfach stark)

I think the other is "A little brother" (Ein kleiner Bruder) Notice the -le added to the end of brider.

"Participate" (Machen Sie mit) They're soliciting your Swabian words and standard German translations that you can provide. Presumably for more ads and coasters like this one.

"For celebrating," "In order to celebrate" (Zum Feiern)

"Family growth" (Familiezuwachs)

"On the Wasen graze rabbits" (Auf dem Wasen grasen Hasen) The "Wasen" being Canstatter Wasen, the Stuttgart fairgrounds where Frühlingsfest and Canstatter Volksfest are held every April and October. The rest of this coaster is an ad for a "Sebastian Blau Prize" contest for any Schwäbisch song you could write. It seems to have expired several years before this coaster found its way into my hands.

Most of these were easy to figure out, but this did help a lot with some unfamiliar words.

Alsatian

Elsässisch is the traditional language of Alsace/Elsass, which was once German but is now part of France. It's closely related to Swabian and Swiss. Ever since the end of WWI, when France decisively took Alsace back from Germany, Alsatian has been largely replaced by French, but there are revival efforts underway. Throughout the center of Strasbourg, Alsace's largest city, known as Straßburg in German and Strossburi in Alsatian, there are bilingual French-Alsatian street signs like you see below...

"Long Street," German Langstraße.

"Half Moon Street." Something I noticed here is that most of these Alsatian street names ended in gass. In German Gasse actually means "alley" but it's pretty common to see it used in the names of any narrow side street.

The top one says, seriously, "Tit Street." (stop giggling, that's a kind of bird) On the bottom is "Little Church Street." Standard German would be Meisegasse and Kleine Kirchegasse.

Since I can't find any Standard German word close enough to Gewerbslaawe I'll just assume the left sign, because of the French version, means "On the Arcade." The one on the right says "On the High Climb," which in standard German would be Am Hohe Stieg.

Bavarian

Bavaria/Bayern is probably the most famous German state, since it is the source of most of Germany's national stereotypes: Lederhosen, Dirndl, the snow-capped peaks of the Alps, Oktoberfest, and most of Germany's most well-known beers. Here they speak what in German is called Bairisch and in Bavarian is Boarisch. The capital city Munich in standard German is München and in Bavarian is Minga.

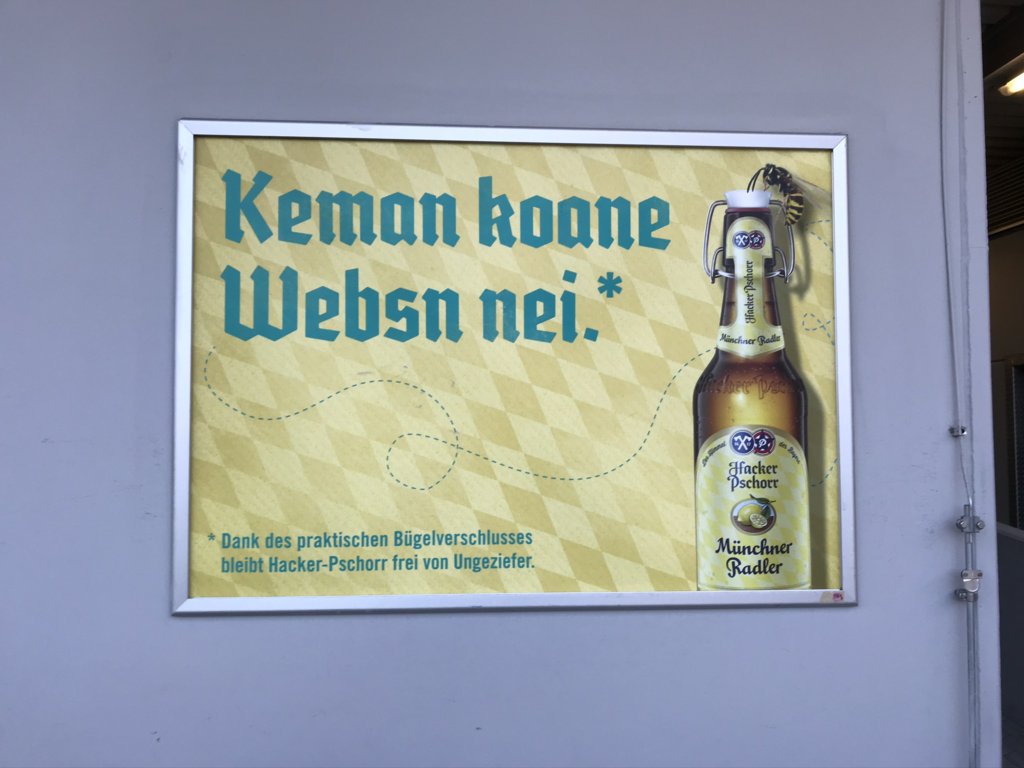

A beer ad at the Garmisch Classic ski resort. I'm really not sure what this says; I know that koane corresponds to standard keine meaning "no" (as in "there is no...") I tried looking up Websen in Google Translate and got "weaver" so maybe that's how Bavarians say "bee"? So maybe this means "No bees come near?" Any help would be appreciated here.

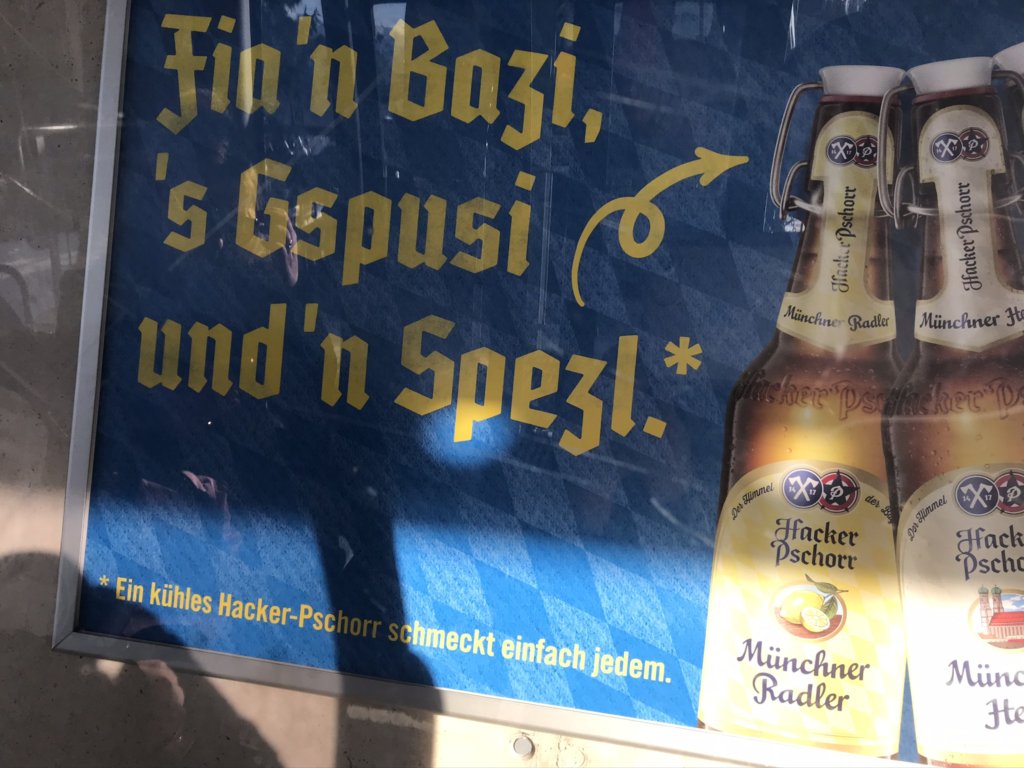

Another beer ad at the Garmisch Classic ski resort.

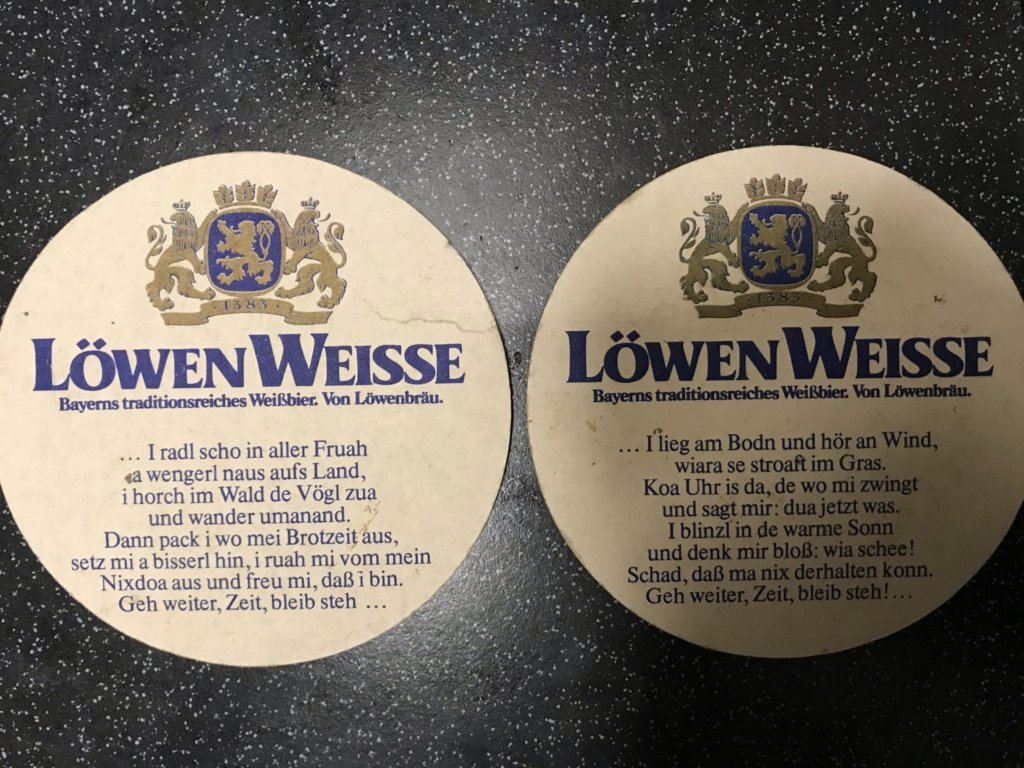

Two Löwenbräu beer coasters which contain excerpts from a Bavarian folk song.

Austrian

I couldn't find a whole lot of written Austrian examples. These two are all I've got. Austrian is close to Bavarian.

An on-mountain restaurant at the Ski Arlberg ski resort complex which straddles the border between Tyrol and Vorarlberg states. The motto means "comfortable, fine, and good!" which in standard German would be gemütlich, fein, und gut.

Griaß di = Grüß dich = hello. Seen on a door to a hotel restaurant in Kufstein, Tyrol.

Bavarians and Austrians greet each other with Grüß dich and Grüß Gott.

Kölsch

This is spoken in Cologne, a huge city in the heart of a huge metro area on the western edge of Germany. Its name is Köln in standard German and Kölle in Kölsch. This is considered “Central German” and as you can see is quite different from what we saw further south.

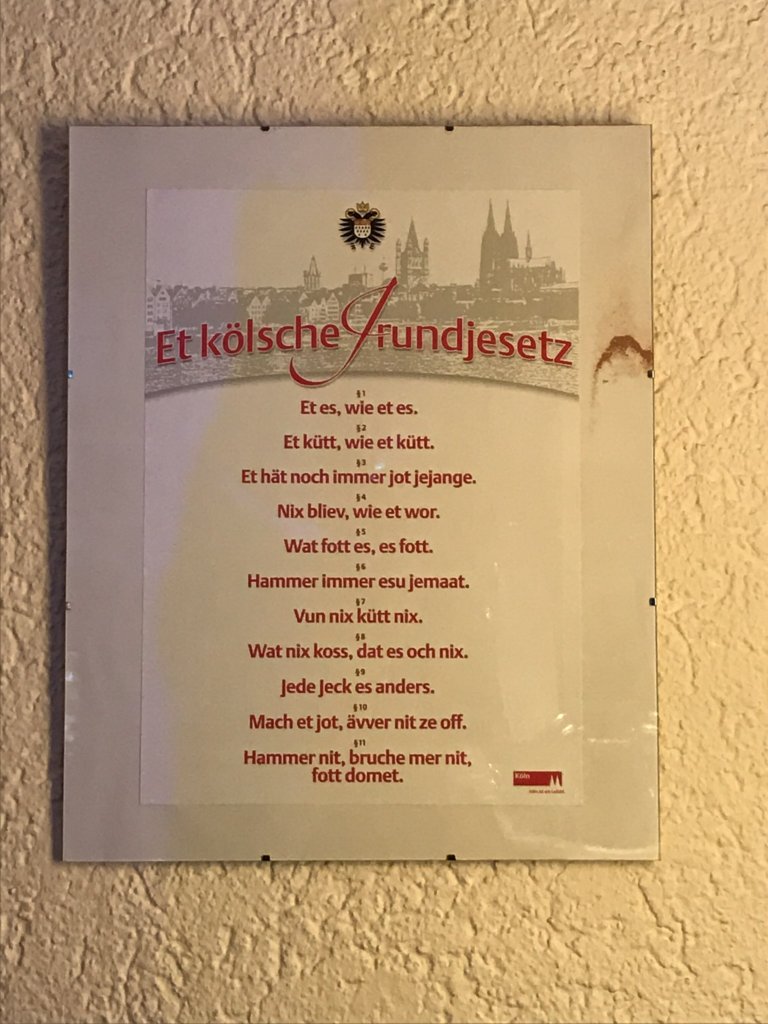

The "Kölsch basic law" (standard German: Das Kölsche Grundgesetz) is a list of local folksy aphorisms like "It is what it is." This unintentionally reveals a great deal about Kölsch; notice, for instance, everywhere you'd see a g in standard German, Kölsch uses a j (pronounced like our y) instead, as in Jrundjesetz and jot (German gut, "good").

This means "Today it rains Kölsch." (standard German: Heute regnet es Kölsch) Here Kölsch refers to the local style of beer.

Coincidentally I found this on a night just a few hours after I finished the 2019 Cologne Marathon, which was 42km/26.2 miles. It says "42km on bare feet through Cologne." Apparently bläck is Kölsch for "bare."

Thanks to the Kölsch Wörterbuch which helped with the translation.

Luxembourgish

Before 1984, Luxembourg only recognized two languages spoken in its borders, French and German, with Luxembourgish only considered a local dialect of German. Since it is now officially recognized as a language it can't be called a dialect anymore, though it still fits squarely in the Central German grouping right next to Kölsch. Even with it's official status, it's still rarely ever written; almost all printed material is in French. What you're about to see here, then, represent rare exceptions to that rule and the only examples of Luxembourgish signage I glimpsed during my day there.

"Great Street" or "Big Street" (German Großegasse or Großestraße; the Luxembourgers, like the Alsatians, seem to favor Gasse as the word for "street")

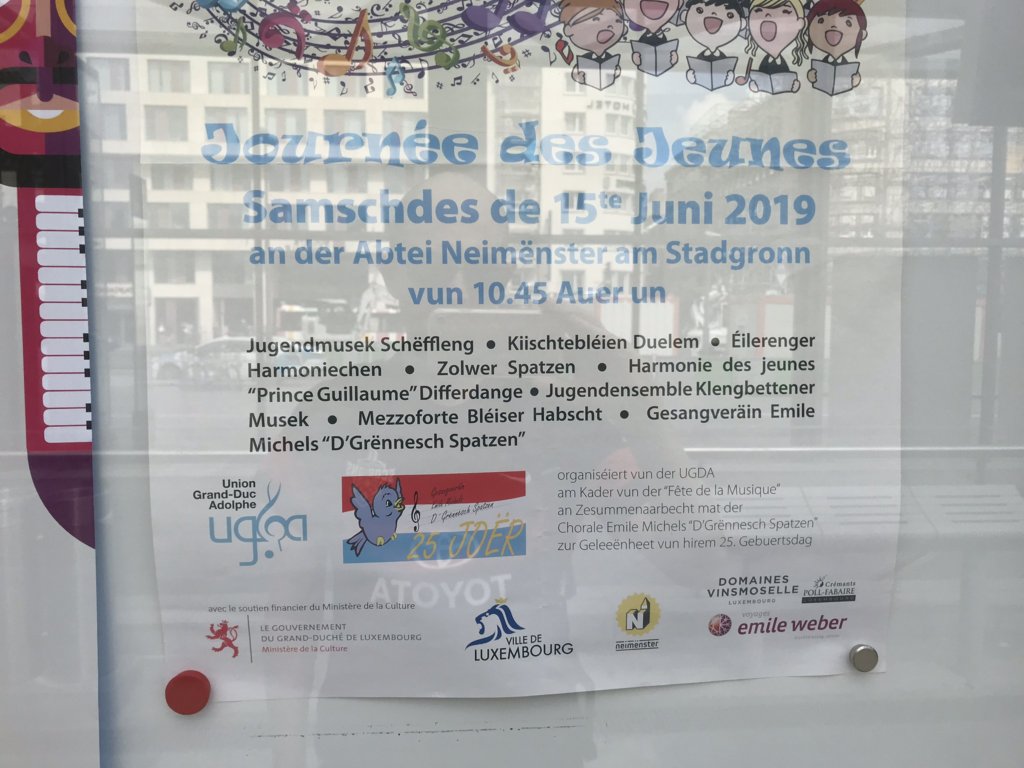

An ad for some upcoming concerts. Almost all of this is pure Luxembourgish, but notice there's a little French in there too. That's Luxembourg.

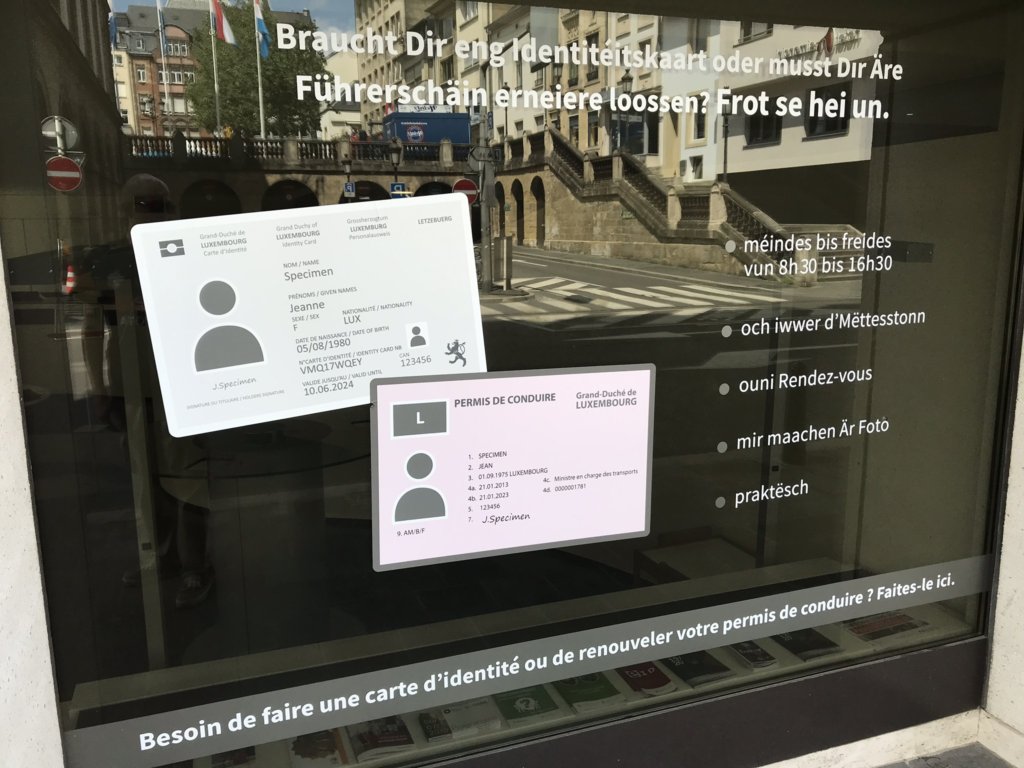

This is a place where Luxembourgers can get their drivers' licenses renewed. Across the top and bottom you see the same sentence in both Luxembourgish and French: "Do you need to get an ID card or renew your driver's license? Do it here."

"We wish you a happy National Holiday!" In standard German that would be Wir wünschen euch einen schönen Nationalfeiertag! This was part of the festivities on June 22, 2019, Luxembourg's annual national holiday, analogous to July 4 in the US.

Ruhr German

Ruhrpott, as they call it, is spoken in the Ruhr area, Germany's biggest metro area. This is a huge metroplex based around the cities of Dortmund, Essen, Duisburg, Bochum, and various smaller cities and suburbs that surrond this cluster. The river Ruhr flows through this area, hence the name. Even though the Ruhr area is well within the Low German area, which we'll look at after this, Ruhrpott is actually a High German dialect with lots of influence from Low German and Dutch. (So does that make it a creole?) This is what the German Wikipedia says; the English Wikipedia just says it's a Low German dialect, but since the English article is very short with no sources cited and the German article is long and detailed and thoroughly sourced, I'll trust the German Wikipedia here.

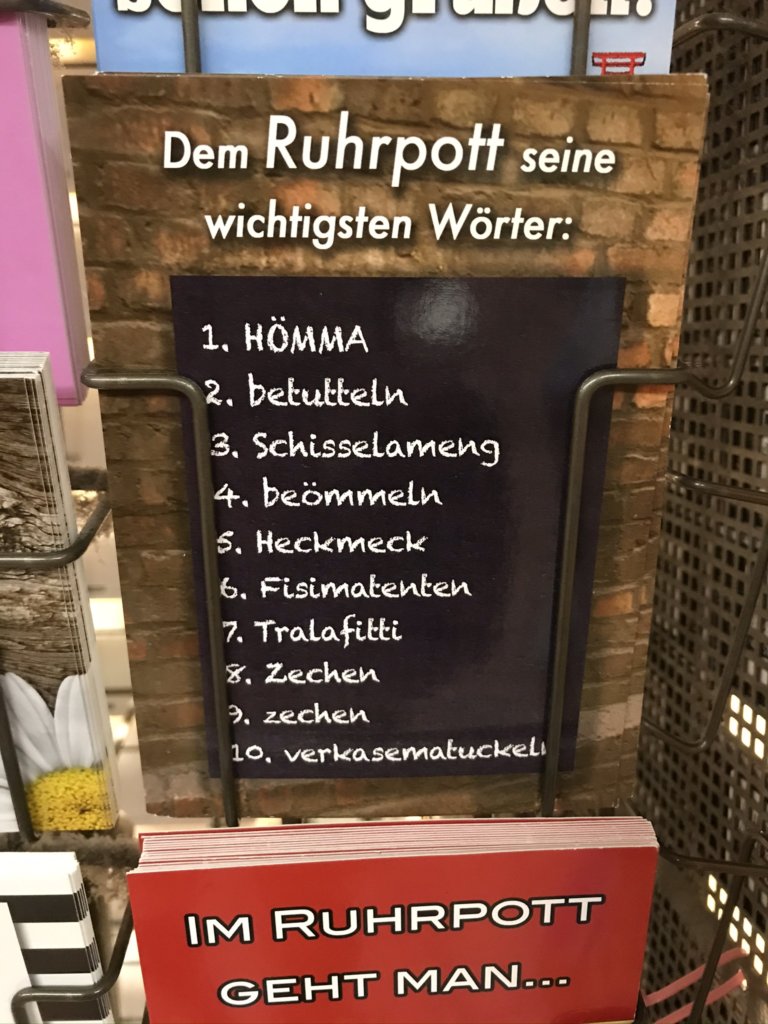

"Ruhrpott's most important words." The first one, hömma, is apparently the most famous Ruhrpott word. It's a contraction of hör mal meaning, more or less, "listen up." From what I can tell, Ruhr people use it the way we would say "hey!"

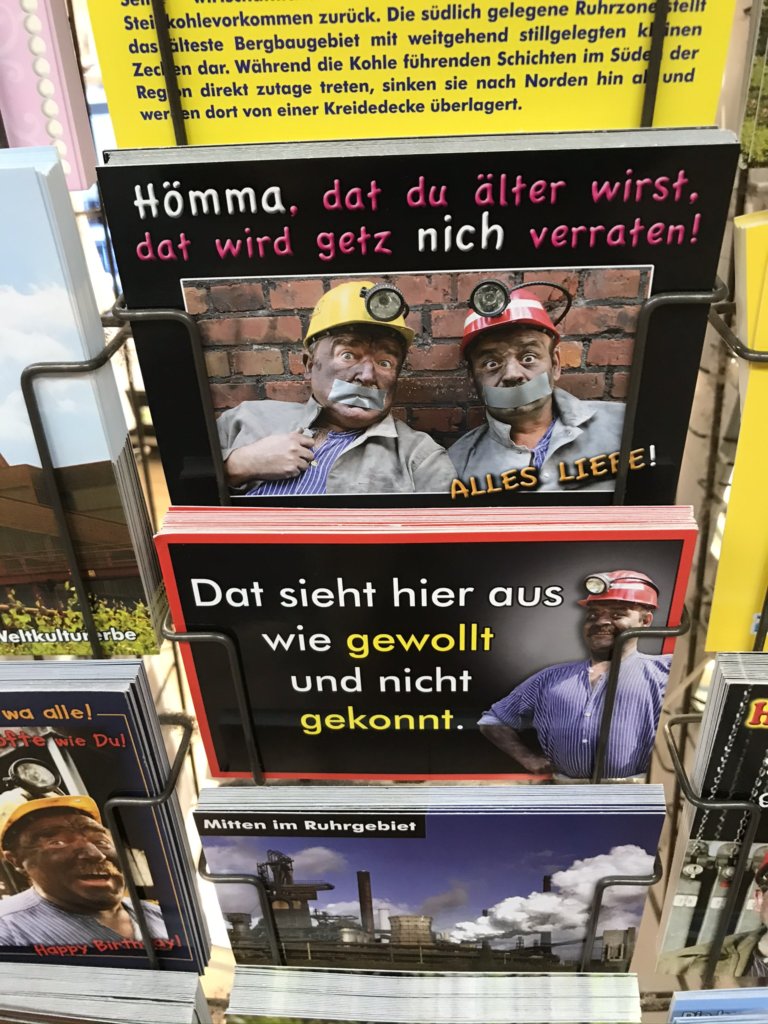

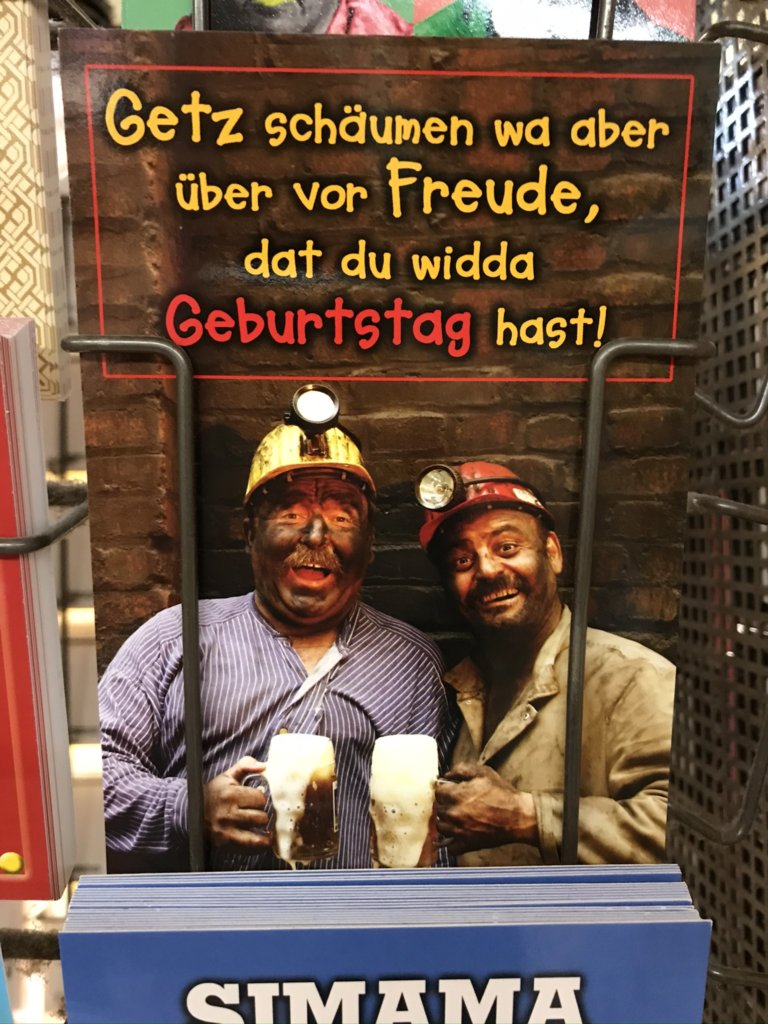

The first is a birthday card. I think getz means "now" (standard German jetzt) and with that in mind, I think the first one is saying "Listen, you'll be older, we won't give that away!" The second is probably "That looks like 'wanted to' and not 'could.'" Notice they say dat instead of das; this comes from Low German.

I'm not really sure how to translate this; I think the it's saying something like "Now we're foaming (boiling? frothing?) but with joy because you're having another birthday!"

And more thanks to this page for its help in understanding Ruhrpott.

Low German

Low German is wholly different from everything else we just looked at, having evolved separately from everything we’ve looked at this far. It’s called “Low German” not because of any social status but only because it’s spoken in low-lying coastal regions. Everything further south is “High German” because it comes from the mountains. The Low German area covers the northern third of Germany, as well as the neighboring Markgröningen area in the Netherlands and some places in southern Denmark. The biggest Low German-speaking city is easily Hamburg, which is where all these examples came from.

Outside the Jungfernstieg U/S-Bahn station in Hamburg. Dat Backhus = Das Backhaus = The Bakehouse.

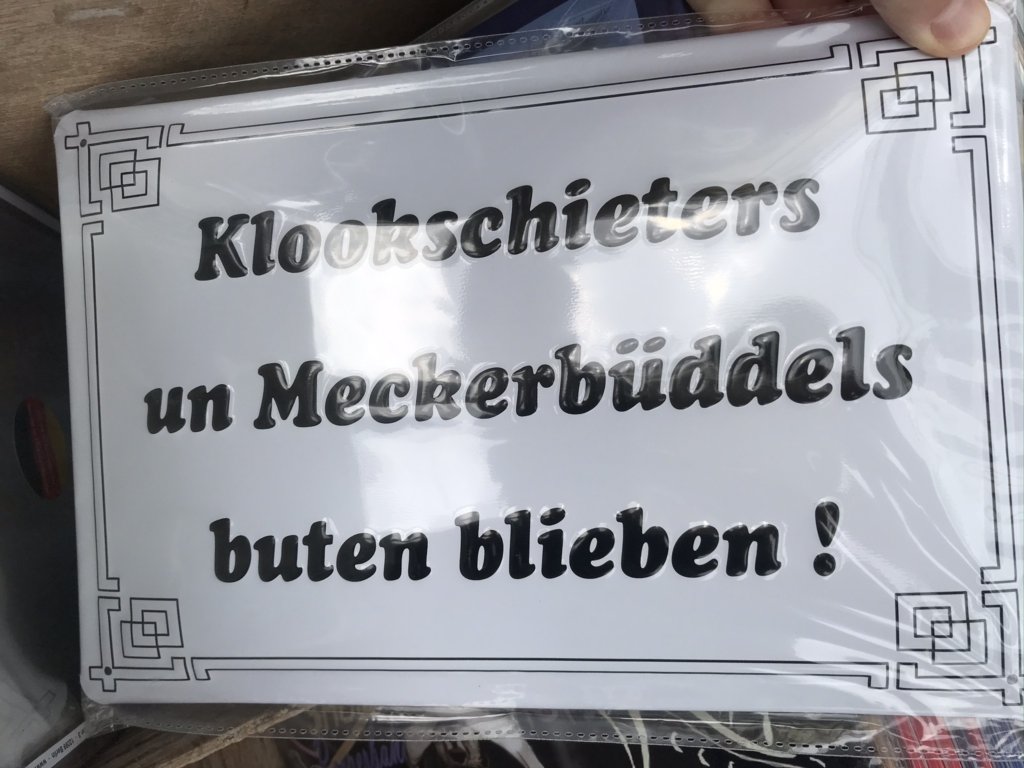

Souvenir for sale at one of the many gift shops on Hamburg's pier. When I saw this I hadn't a clue what it said. After some Googling and looking around the Low German Wiktionary, I've figured it out: "Smartasses and whiners stay outside!" I should've bought one.

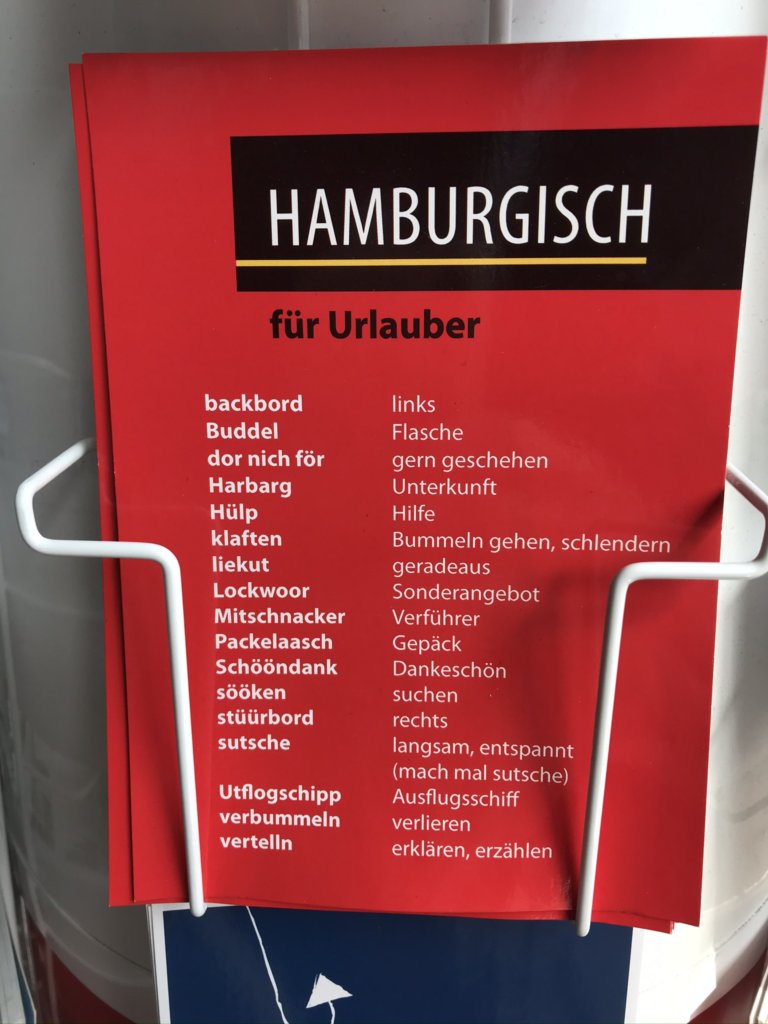

Postcard for sale at a gift shop on the pier. "Hamburgish for vacationers." It's a list of "Hamburgish" Low German words with their standard German translations. A few of these make me wonder how serious it is; notice the translations for "left" and "right" are backbord and stüürbord. In other words, "port" and "starboard." Is that really how Hamburgers say left and right?

"Hello Hamburg!" Typical ad displaying Hamburg's favorite greeting/catchphrase.

In Hamburg the most common greeting is moin, sometimes duplicated as moin moin. It's such a famous local catchphrase that, much like aloha in Hawai'i, it's become part of advertising, including tourism ads. I also heard people saying it in Kiel.

So how widespread are the so-called dialects, after decades of standardization? It really depends on the region. This article reveals that only 2.5 million people speak Low German. That's not a lot, when you consider that's only half as many people as live in the Hamburg metro area, and the traditional Low German area covers about a third of Germany. But, it also says that Low German has declined much more in the last century than other "dialects" to the south; Bavarian has 13 million speakers, it says. Meanwhile Swiss German is famous for having no stigma attached to it, coexisting alongside Standard German with the two languages being used in distinct situations in life; quite a contrast with the situation in the north. So for now it sure looks like the regional German languages aren't going to die out quite so quickly, at least not in the south.