Salzburg is a small city in Austria, the capital of a state also named Salzburg. At just over 100,000 inhabitants it's on a similar scale to Luxembourg City. It's mostly famous for being the home town of the legendary composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and more recently for a classic movie that was filmed there, "The Sound of Music." I have little interest in either of these things, though, so I'd wager this travelogue has fewer mentions of Mozart or the Von Trapps than any other about this city you're likely to read.

Since moving to Germany, I'd crossed the border into Austia many times, always for snowboarding trips. I've been down the slopes in quite a few Alpine ski resorts throughout the Austrian Alps, and I just wanted to visit that country at least once for something else. I did get to see more on a couple of those other trips, including a Krampusnacht festival in Sölden and some bar hopping in Kufstein, but those were still just minor diversions. This excursion would be my first time backpacking through an Austrian city like in any other place I've already written about.

Saturday, August 15, 2020

Trains, of course. I'm really getting some serious mileage out of my BahnCard. It took about four hours to get there, first riding an IC (a standard, non-high-speed InterCity) from Stuttgart to Munich, and then a slower regional Meridian (a service that connects several towns in the Bavarian and Austrian Alps) from Munich to Salzburg. It was about time for lunch when I stepped off that last train, so I got some kind of mozzarella & tomato sandwich at Natoo, a pretty good restaurant in Salzburg's train station.

Salzburg--not just the city but the whole state, of which the city is the capital--was for centuries a Prince-Archbishopric. That means that it was a monarchial state just like nearly all the other German states in those days, which were ruled by kings, dukes, counts, princes, and the like, except that instead of a dynasty or royal family passing down the right to rule, the ruling prince of Salzburg was whoever the Catholic Church appointed as archbishop over that area. Getting to run not only the local church hierarchy but also the government...that could be either a fringe benefit or a burden depending on how you feel about it. This actually wasn't quite as unusual an arrangement as you might think; there were plenty of other prince-bishoprics and prince-archbishoprics in those days, Liège in Belgium comes to mind.

Like countless clergymen back then, the Archbishops of Salzburg didn't take the whole "celibacy" thing seriously. They may not have married or left any legal heirs, but they did openly have mistresses. One ruling archbishop, Wolf Dietrich Raitenau, had a palace built for himself and his mistress Salome Alt in 1606. That palace is Mirabell. It's mostly worth a visit because of the gardens behind it.

I've been told, by people who've actually seen the movie, that this was in "The Sound of Music."

The next place I found myself was a museum simply called Salzburg Museum. This museum is dedicated to the history of the city and especially to its century-old tradition known as Salzburg Festival.

The annual Salzburg Festival was celebrating its centennial this year, since it was started back in 1920 by theater impresario Max Reinhardt, composer Richard Strauss, and playwright Hugo von Hoffmansthal. There's not a whole lot I can write about the Festival, since I didn't experience any of it, and all I know is what I saw in the museum which I went through relatively quickly. From what I can tell, it seems to consist of a slew of operas, classical music performances, and plays staged throughout the city. Kind of like a highbrow version of Fiesta San Antonio. The museum is full of photos, copies of newspaper articles, costumes, reproductions of stages, and such from over the decades. It seems the most famous event of the festival is a play called "Jedermann" ("Everyman") written by the aforementioned von Hoffmansthal.

I unfortunately didn't get the chance to experience any of the festival. I can't really say why other than that I was just never in the right places at the right times. I'm pretty sure they didn't stage any performances of "Everyman" while I was in town.

Well, after that museum my next stop was one place that is obligatory for me, the Stiegl brewery. Get ready to learn a few things about beer brewing...

It was a little bit of a hike to Stiegl-Brauwelt (meaning "Stiegl Brewworld") which is a little bit outside of the city center. In the gift shop I paid for a tour ticket and discovered that there was no guided tour; instead what you do is download an app called "Hearonymous" to your phone and through that you listen to recorded narrations at specific spots on the tour as you walk through at your own pace. I've even kept this app because I can still listen to the narrations even here at home.

So, how do they make our delicious liquid gold? It all starts with cereal grains. You can make beer with any kind of grain, but most beers--lagers, pilseners, bocks, etc--are made from barley while hefeweizens, of course, are made from a mix of barley and wheat. The grains must be first be malted; that is, they're soaked in a vat of hot water for over a day, allowing them to germinate until a certain point in the process when they're immediately removed from the water and dried before they can germinate further. The resulting dried, partially-germinated grains are thus called malt. Making malt is actually an intensive process itself; for this reason, most breweries don't make it themselves, but buy it from malthouses. In the first step of the brewing process, the malt is "mashed," that is, mixed up with water in vats called mash tuns, where sugars leech out of the malt and into the water.

These are hop plants. Hops give beer its bitterness and much of its flavor and aroma. After the malt has been mashed, the mash is then purified, or lautered, in another vat where the spent solids are separated from the sugary liquid, called wort. The hops are added to the wort at this point. Did you know that hops are closely related to cannabis? Really! Hops come from the genus humulus, which is part of the family cannabaceae along with the genus cannabis.

Yeast gets added in the next stage, after the wort is thoroughly hopped. It's easy to forget that yeast is a living organism. Not a part of a living organism, like grains and hops which are parts of plant, but a whole lifeform in itself. It's a single-cell fungus, and what you see here is a cutaway model of a yeast cell.

Yeast is the fermentation starter; its purpose is to split the malt sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide. Once that gets going, what happens next depends on whether you're brewing a "top" or "bottom" fermented beer. If the yeast rises to the top, it's top-fermented, as in hefeweizen, alt, kölsch, stout, and porter, and it will ferment at 10-22°C (50-71.6°F) in about half a week. But if the yeast settles to the bottom, it's a bottom-fermented beer, such as lager, pils, märzen, and bock, and it will ferment for a whole week at only 7-10°C (44.6-50°F).

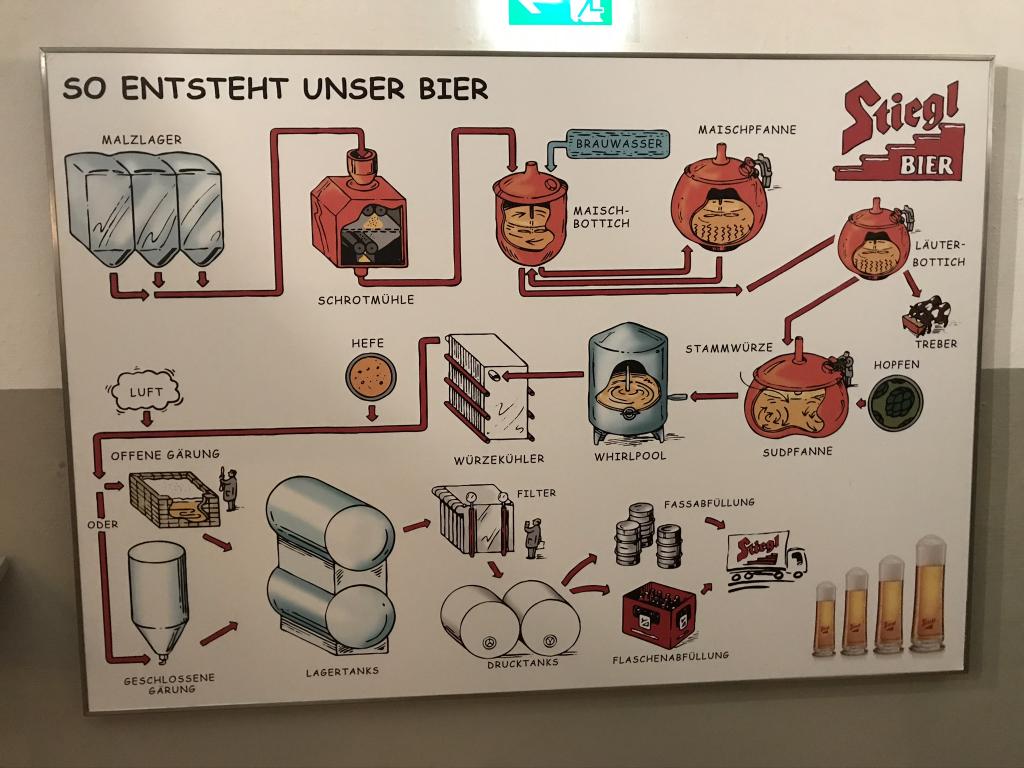

Was all this a bit bewildering? Well why don't I let them explain the whole thing? This is a chart of the whole brewing process. In the top left you see the malt (Malz) in the malt silos (Malzlager), it gets crushed in the mill (Schrotmühle) and mixed with brewing water (Brauwasser) in the mash (Maisch) tuns. In the lautering tun (Läuter-Bottich) the wort (Würze)--that is, liquid with malt sugar in it--separates from the malt. The worn-out sugar-less malt then gets fed to cattle while the wort get hops (Hopfen) added while being boiled in the Sudpfanne. This new hoppy mixture gets stirred up in the whirlpool and then cooled off in the cooler (Würzekühler) after which it gets yeast (Hefe) added to start the fermentation. It spends the fermenting time mentioned above in either the open tank (offene Gärung) or the closed one (geschlossene Gärung). What comes out of this is called "green beer" and needs to be matured for a month or so in storage tanks (Lagertanks).

Notice that it goes through a filter near the end. This filter removes all the proteins, tannins, and yeast left over from the brewing. At this point in the tour they actually had unfiltered beer you can taste; there's a whole bunch of small glasses there and a tap you can fill one with. Unfiltered beer looks rather cloudy, while filtered beer is clear. Many breweries, including Stiegl, sell unfiltered beer alongside the filtered. If you ever see any beer for sale anywhere described as a "Kellerbier" or "Zwickl," that's unfiltered.

This is a beer cellar where specialty varieties are maturing. Usually they use steel vats for most beers, but some types, especially those with high ABV, get this kind of treatment. These barrels were previously used to store liquors like vodka and tequila, and the residual flavor rubs off a little bit on the beer.

So about that malt. It takes a lot of work to turn grains into malt, it seems. So much that most breweries these days don't even make their own malt, they just buy it from businesses called malthouses which exist solely to turn huge amounts of grain into malt and sell it to breweries. Stiegl makes some and buys most.

This is a kiln that was once used to dry the malt after soaking and germinating. Malt has to be stirred up in here continuously for 24 hours. Back in the day they needed workers to keep stirring it for that long (presumably they worked in shifts, I would hope) in temperatures around 50°C (122°F). Not exactly an easy task. Nowadays they have machines to do that work.

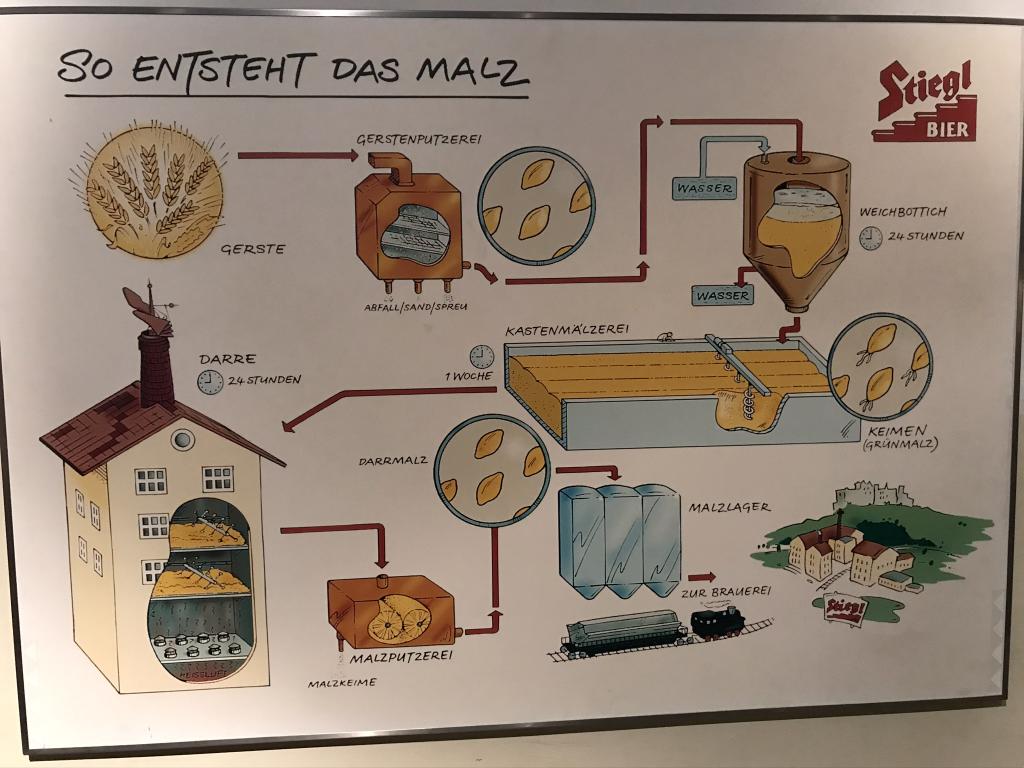

This is the whole malting process. Since this is such a long process you can understand why most breweries outsource this work to malthouses. The grain is soaked in the Weichbottich, germinates in the Kastenmälzerei, and dried in the kiln (Darre) in the bottom left.

Further on they described what a big deal it is that Stiegl makes beer with "12 degrees of wort." What does this mean? As the narrator explained, it means that 100kg of wort has 12kg of malt extract in it before fermentation. Apparently that's the most you can have in wort, because he kept saying "the full 12 degrees" and also that Stiegl only used less during times of crisis like WWII, and that most other Austrian breweries use less.

There sure are a lot of steps to the brewing process! It's amazing to think humans have been doing this for so many millennia. The ancients never knew anything about the chemical reactions behind all of this; they only figured it out through lots of trial and error (or as I like to say, throwing shit at the wall and seeing what sticks). It probably all started when someone in ancient Sumer made a pretty good drink after messing about with yeast and water and grains. Through the ages, generations of brewers made little accidental discoveries, unintentionally finding one way or another to make a better product than before as they tinkered with the process. And now after a few thousand years breweries like Stiegl are brewing thousands of liters of a drink that the Sumerians could only dream about.

After the tour, I bought myself a half-liter beer glass and some beer flavored mustard in the gift shop. Then I stopped by their restaurant to drink some of the product I just learned so much about.

A three-beer sampler From left to right: Goldbräu, Paracelsus Bio-Zwickl (unfiltered), and Columbus 1492 (Stiegl was founded that year), all in short, narrow 25cl glasses. This was not at all my first time drinking Stiegl; I've had I don't know how many liters of it at various Austrian ski resorts, though I think that was all Goldbräu.

The brewery experience over, I headed back downtown, where I stopped for dinner in an interesting restaurant called My Indigo. It was a real trendy-looking place serving bowls and soups with whatever meats and vegetables you choose. I don't remember exactly what I had, except that it was a bowl with chicken and nearly every vegetable they had.

After that I stopped in a bar called Darwin's Café Bar. Here I had a coffee and a beer called Zipfer. I don't know why this is...they have the Stiegl brewery in town, which exports its beer all over the country and over the borders, but in the bars I visited Zipfer seemed to be more abundant.

Before moving on I had to check in at my hostel, another a&o. I had had good experiences with two a&o hostels in Hamburg, so another one here seemed like a good bet. I checked into my room, stashed my stuff in a locker, and then headed out to hit a few bars.

There's another brewery in town with a storied history, Augustiner (no relation that I know of to the more famous one in Munich). Their brewery has a Biergarten that I wanted to check out. So I looked up its location on my map app and saw I'd have to take a bit of a hike...and a bit of a hike I took to get there. I discovered, to my dismay, that the place was packed on a Saturday night and I'd probably be waiting all night to get a place to sit at, much less a beer, so I took another bit of a hike back downtown. This place would have to wait until the next day.

Eventually I found myself at Shamrock Irish Pub. I didn't actually have anything Irish here; I just had an Edelweiss Hefe, which was a pretty good wheat beer, and another Zipfer. They didn't have Stiegl on tap either! They did have live background music, provided buy one guy with an acoustic guitar. He played stuff from all over the spectrum. What I remember the most was when he started one song by strumming certain familiar chords, and I was trying to guess what song this was going to be. I thought maybe, based on the last few songs he'd played, it was ZZ Top's "Cheap Sunglasses," or maybe Black Sabbath's "The Wizard," but then he started intoning "Go shorty, it's your birthday, we gonna party like, it's your birthday, sip Bacardi like, it's your birthday..." I realized I was way, way off.