Saturday was a pretty eventful day which was mostly taken up by the Gran Museo del Mundo Maya, dedicated to the civilization that once controlled the Yucatán peninsula, followed by the reason why I was in Mérida when I was--the Rock 'n Roll Half Marathon.

Saturday, November 4, 2017

So it was Saturday morning. The Rock 'n Roll Half would be that evening. Because I'd be running such a race, that meant all my food intake rules were temporarily suspended and I could go crazy with the carbs! I went back to El Gran Café, the restaurant where I had been the morning before, for breakfast, though this time I really loaded my plate with pancakes.

After breakfast there was a place I wanted to visit in this city: el Gran Museo del Mundo Maya, that is, the Museum of the Mayan World, a museum dedicated to all things Mayan. To get there, I tried using the means I usually do in cities I visit, public transit. This was a mistake. Wikipedia says "Bus transportation is at the same level or better than that of bigger cities like Guadalajara or Mexico City." Maybe if one of you used a bus there it might work better for you, but for me it was a waste of time. The bus I got on, which I thought was on the right route I'd researched ahead of time, was not so much a bus as a huge van, and it spent over an hour twisting and wending its way in a bewildering, byzantine route through one residential neighborhood after another before finally depositing me back where I started. At no point did it ever go anywhere near the Maya museum, so I just took a taxi there.

Now then, the Maya museum. The entire Yucatán Peninsula, as well as all of the modern countries Guatemala and Belize, used to be ruled by the ancient Mayans. That's not to say that the Mayans are gone; Mayan heritage is everywhere in these parts, and there are still millions of Mayans living here who speak Mayan as their first language.

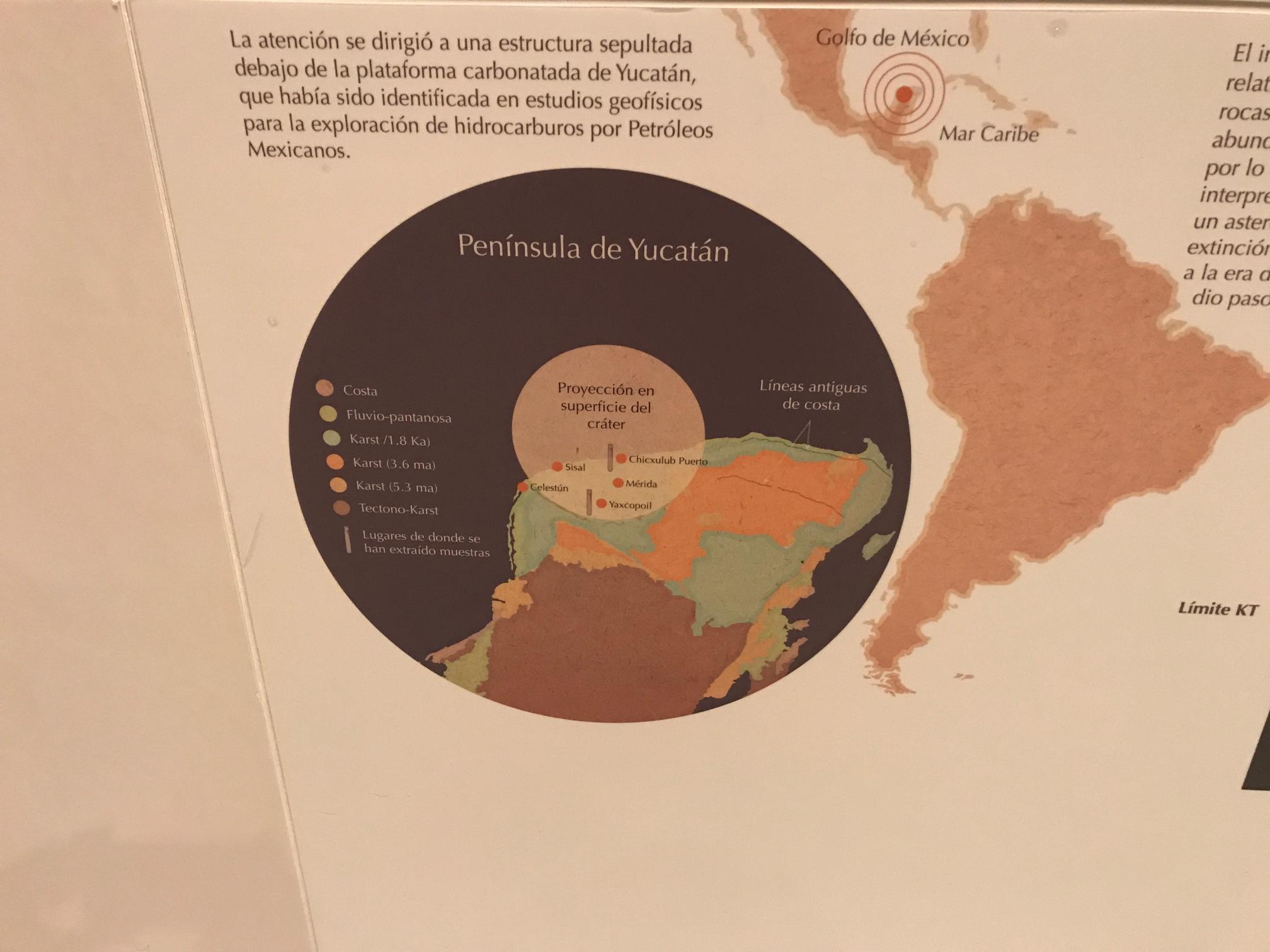

The first part I walked through wasn't so much about the Mayans but about something that happened millions of years before the Mayans, or any other humans, even existed--the Chicxulub asteroid impact, which caused the massive climate changes that caused the dinosaurs to go extinct.

The crater is, today, mostly filled with an eon's worth of sediment, leaving only the outer ring easily discoverable. As Bill Bryson's A Short History of Nearly Everything explained it, the outer ring of this crater was discovered by Pemex (Mexico's state-owned oil company) back in 1952 and for decades was assumed to be a volcanic formation. It wasn't until 1991 that geologists determined it was actually a meteor impact site, which just happened to coincide with the end of the Cretaceous period and the extinction of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

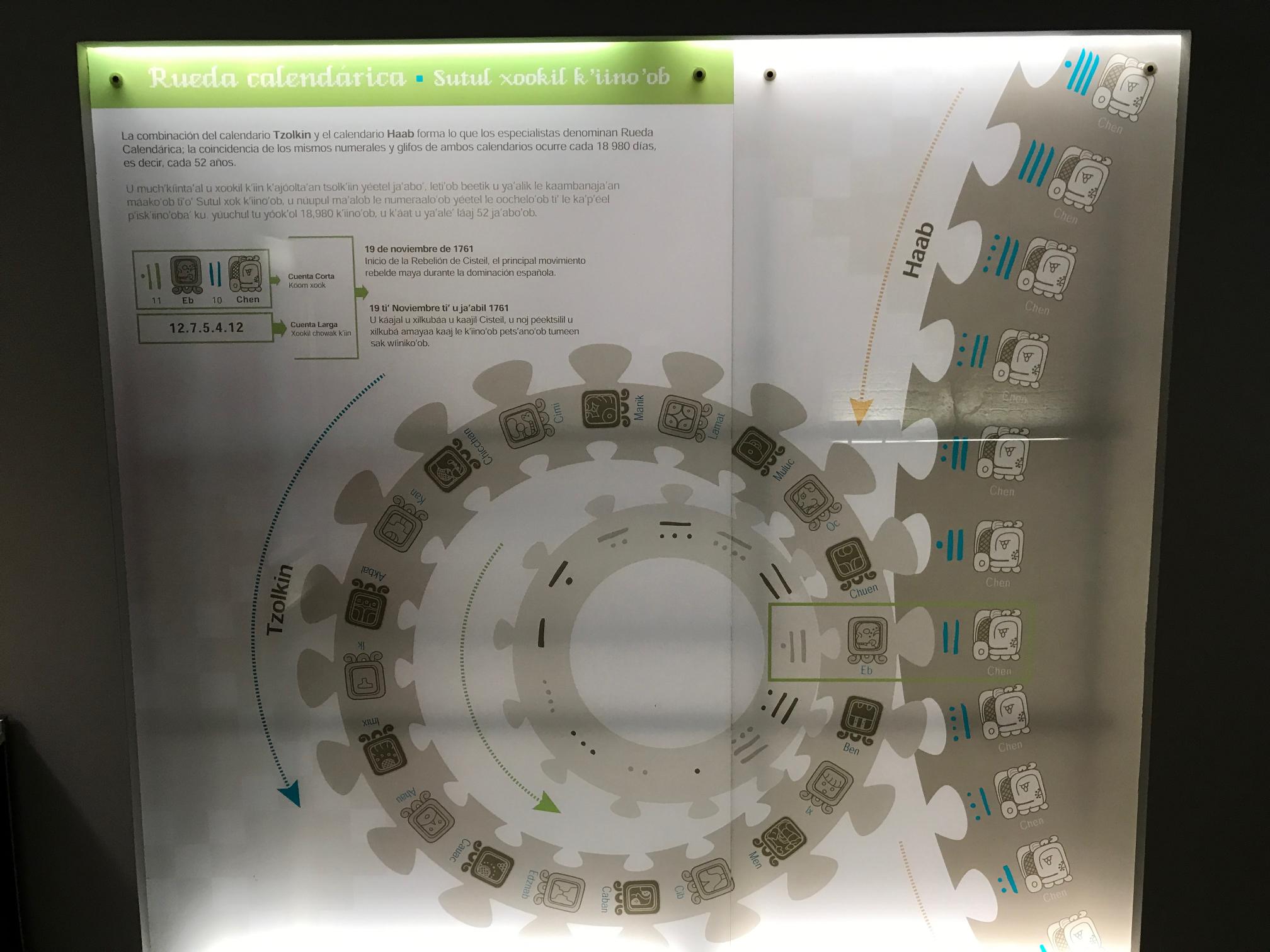

This shows how the "short count" or "calendar round" works. It's actually a combination of two systems, the 260-day Tzolkin on the left and the 365-day Haab on the right. With the Tzolkin, the number (inner wheel) and the glyph (outer wheel) both increment each day, while on the Haab glyphs represent months, of which there are 18. Each of these 18 months contained 20 days, a total of 360 days, and at the end of the year there were five more "unlucky" days. Every day all three wheels increment. So here the dials are set to 11 Eb, 10 Chen, and the next day would be 12 Ben, 11 Chen. It takes 18,980 days--about 52 years--to go through every possible combination, after which the cycle begins again.

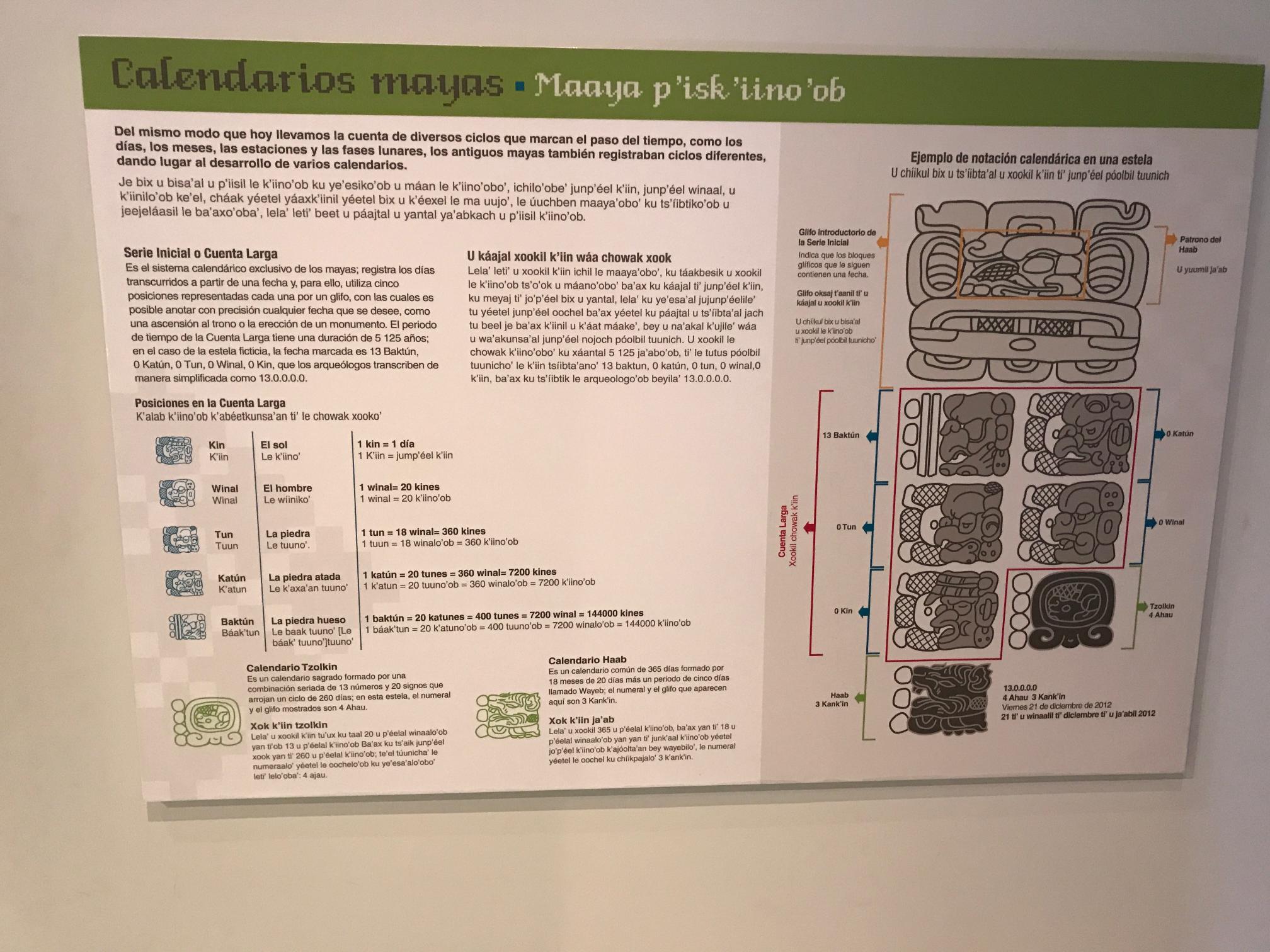

This explains the other Mayan calendar system, the "long count" used for measuring periods longer than 52 years. As you can see there are five units of time: the kin (day), the winal (20 days), the tun (18 winal or 360 days), the katún (20 tun or 7,200 days; or 19 years, 8 months, 20 days give or take a day or two), and finally the baktún (20 katún or 144,000 days; about 394 years, 3 months, 4 days). Remember back in 2012 when a lot of gullible people thought the world was going to end on December 21? That was based on a misunderstanding of this calendar. December 21, 2012 was never supposed to be the end of the world; it was merely the last day of one baktún.

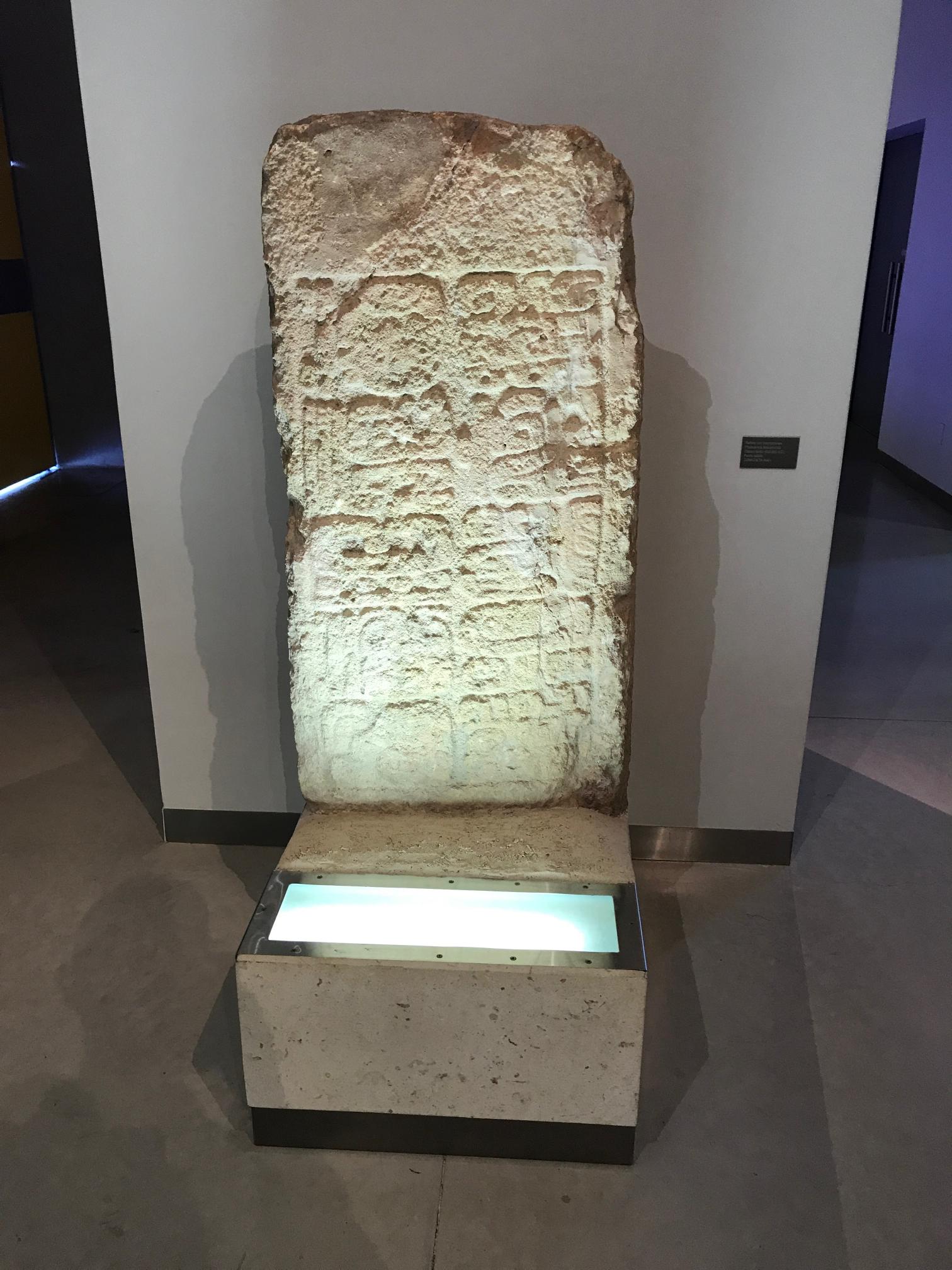

An example of a stela displaying the kind of long-count date explained in the preceding diagram.

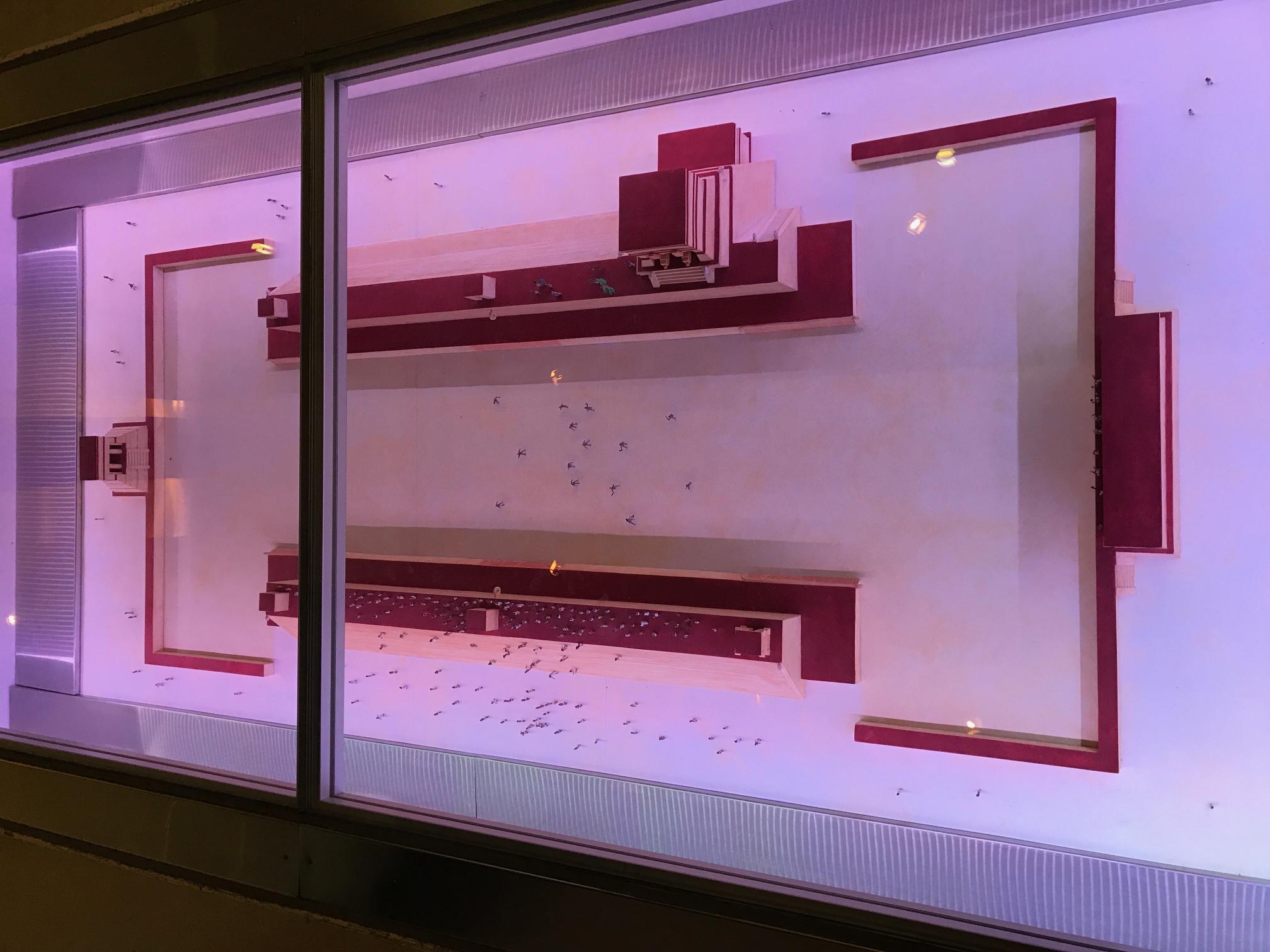

This is a model of the ball court at Chichén Itzá, which I visited in person two years earlier. Most of the Mayans' big cities had one of these, although they varied in size. The ball game was somewhat similar to basketball; two teams of players bounced a big rubber ball around, which they could only touch with their elbows and knees, having to lob it through one of the goal rings you can see hanging from the walls in the middle of the court. No one's sure today what the exact rules were, but similar varying versions of this game were popular in other Mesoamerican societies as well, and are still kept alive by indigenous communities across Mexico and Central America.

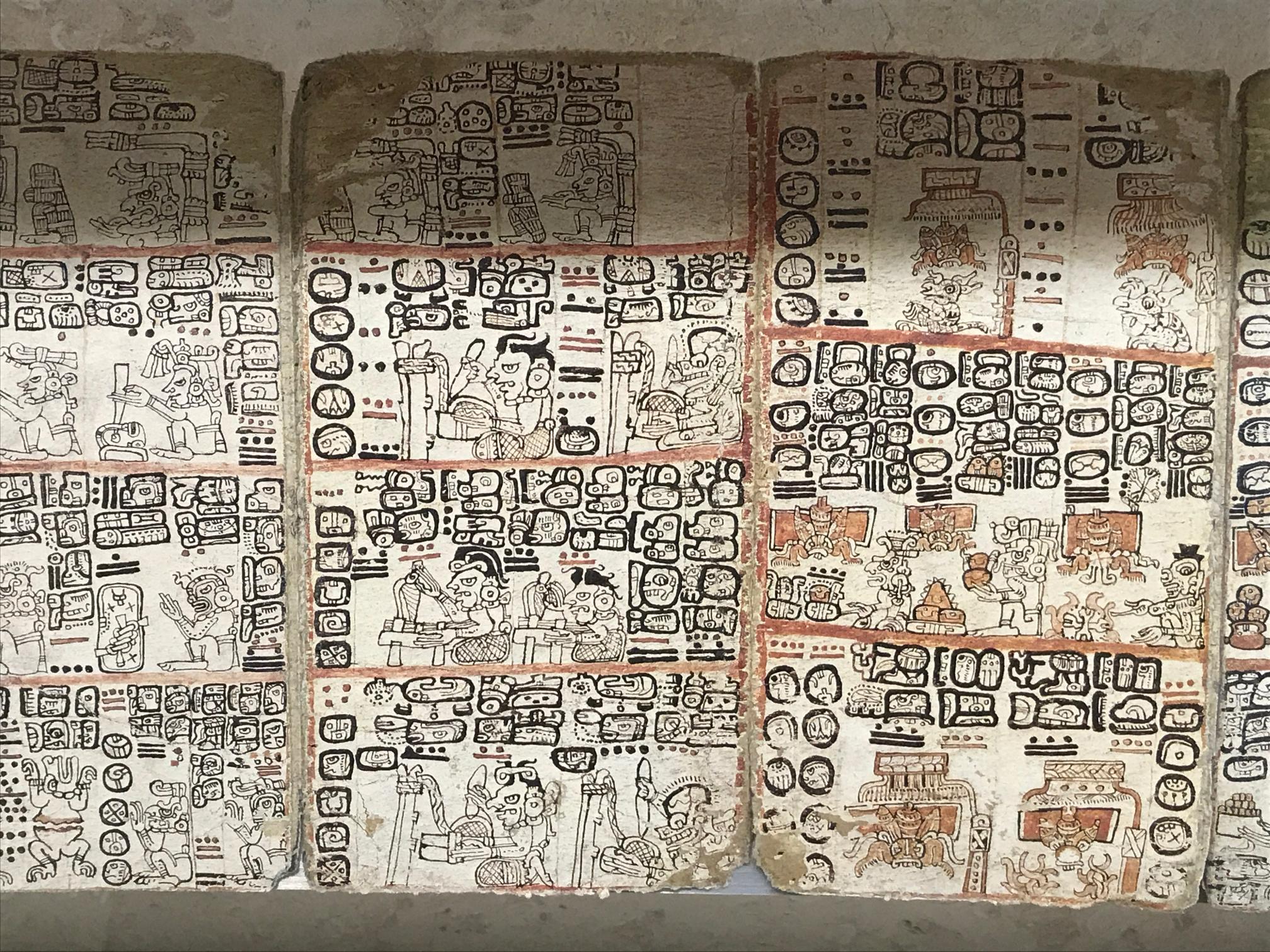

These are pages out of what was essentially an ancient Mayan Farmers' Almanac. Mayan writing has always fascinated the hell out of me. Unlike their Aztec neighbors to the north, or the Incas down in Peru, the Mayans developed a pictographic, hieroglyphic writing system which was just as advanced and complex as what the ancient Egyptians devised, or what the Chinese and Japanese are still using.

After all the Mayan history, I stepped out of the museum with three and a half hours before the race. Just up the road from the museum was a huge shopping mall. This outer fringe of the city had a noticeably different feel than the central city I had spent most of my time in. While the city center was more, to me, reminiscent of an old city in eastern Europe, this part looked like typical American suburbia. I found it more comparable to Plano, Texas, or Papillion, Nebraska, or...insert whatever 'burb you're most familiar with.

Since I had that half marathon coming up and I was still consuming fuel for it, I stopped somewhere I almost never eat at: Krispy Kreme. Yes, there was a Krispy Kreme here in this mall in Mexico, a small stand right inside the entrance to one of the anchor stores. After having a couple glazed doughnuts, I walked through the store and into the mall...

Yes, in this blazing hot corner of the world they actually have an ice rink.

I stopped for some coffee and a butter croissant at the coffee stand you see at the bottom of that picture. After that, it was time to head back to the hotel and prepare for the big race.

The 21-kilometer run--we're in Mexico so it's measured in kilometers not miles--started at 5:30 pm at one of the roundabouts on the Paseo de Montejo. The route went through most of the city center and through a few public parks, and then stuck to the Paseo de Montejo as it went north out of the center to the suburban outer edge. Since I hadn't visited that part before I ran past many things there which I didn't know about, which I wouldn't have the opportunity to check out on this trip, like a Belgian restaurant. Oh well...

One thing I had been a little curious about: how would they handle water stops in a country where "don't drink the water" is an unofficial national motto? Instead of cups of water (as in the US) they hand out these clear plastic sacs that are square shaped, about six inches on each side, and contain about as much water as you can typically fit in a plastic cup. There's no obvious way to open one; apparently what you have to do is tear off a corner with your teeth and then drink out of the resulting hole. I've never seen this anywhere else before or since.

Since this was a Rock 'n Roll Half Marathon, there were plenty of local bands playing. And since this was Mexico, they were playing Spanish rock which I hadn't heard before; how much was their own material and how much was covers, I have no idea.

The race ended not too far from the starting line, at a stadium called Estadio Salvador Alvarado. My time was 2:18:12, which is pretty average for me. They had free beer, of course, which was made by Sol. I thought it was pretty weak, and decided a stop at La Bierhaus was in order before turning in for the night.

If my life were a novel, this would be foreshadowing. I would find myself moving to Germany less than a year after this trip, but at this point I had no idea whatsoever that was going to happen. I had never heard of Mönchshof before, but I had seen all these bottles all over the shelf with that then-unfamiliar logo on it and wanted to try one. Here in Stuttgart one can find Mönchshof in every supermarket--it's made in Kulmbach, Bavaria, which isn't too far away--so I've drunk an awful lot of it over the last 18 months. I also had no idea whatsoever at that time how to open this bottle, because I had never seen such a thing before. It turns out this is a pretty typical beer bottle in Germany.

Other articles in this series:

- Yucatán 2017 Part 1 - First Impressions of Mérida

- Yucatán 2017 Part 3 - Uxmal

- Yucatán 2017 Part 4 - The Cruise